Largo’s Long Career: For the Good of Gopher Snakes

Some people look at animals in zoos and aquariums and wonder if they need to be there instead of in their natural environments. I can understand that, and as a science educator at the Sea Center, I talk to people with these inquiries every day. It motivates me to illuminate the important roles that animals in human care at educational and research institutions can play.

Ambassador animals at zoos and aquariums connect humans with non-human beings in a way no virtual experience can replace. Their real presence—experienced safely and up close—has the power to create empathetic emotional connections between animals and humans. Ambassador animals draw people in to listen to the stories educators tell about their wild counterparts. They bridge the gap between abstract concepts about wildlife and the tangible experience of seeing—sometimes even touching—another living creature. They are living proof of what conservation is all about.

At the Sea Center, I work with our naturalists and volunteers to create meaningful connections between guests and nature, through touch pools and exhibits. Enrichment is an important part of both how we care for animals and how we talk to the public about them. It's a process aimed at finding new and creative ways to improve the lives of animals in human care, informed by scientific knowledge of their needs. By making changes to their surroundings, enrichment offers animals choice and encourages species-specific behaviors.

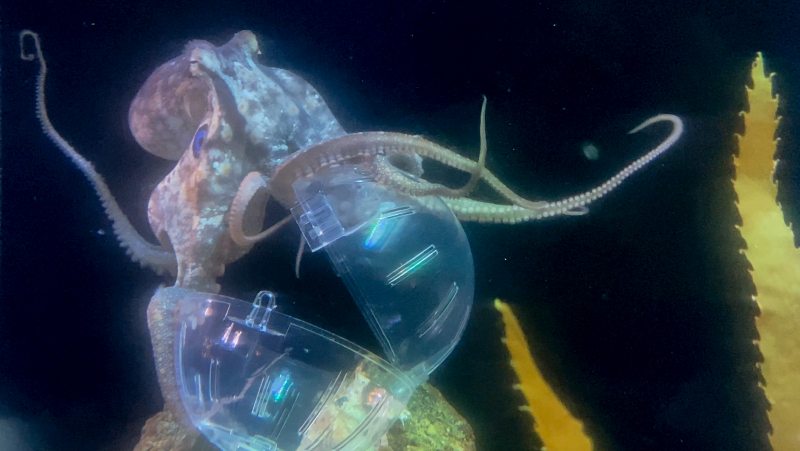

The Two-spot Octopus getting some enrichment: food inside a locked ball offers the chance to solve problems and experience novel tactile stimulation, mimicking aspects of the hunt for prey.

Educating guests about enrichment can expand their perceptions of what animals need, how we relate to them, and the professionalism and expertise involved in their care. I’ve focused on enrichment for several of my graduate program projects (I’m working on a master’s degree) because it helps people understand that, like us, animals have complex needs that require diverse approaches to meet them.

My graduate projects have focused in part on how exposing the public to the concept of enrichment for reptiles and amphibians helps people understand and relate to these animals. This might come as a surprise given there are none of these at the Sea Center. But ever since I conducted research on the call behaviors of small chorus frogs, I’ve been captivated by this group of animals. When I tell people about my affinity for reptiles and amphibians and about the work I’ve done with them, I get responses of confusion, disgust, wonder, and curiosity. These responses motivate me to find ways to inspire others to appreciate reptiles and amphibians as much as I do.

Seriously, what’s not to love? Photo by Gabe Anderle

At the Museum—sister campus to the Sea Center—I met Largo the Pacific Gopher Snake. For over eight years, Largo has been a beloved member of the Museum team, educating and inspiring visitors to see snakes as something more than creatures that slither. Largo is now heading into a well-deserved retirement, so I wanted to reflect on the lasting impact he has made as an ambassador animal, and take time to share the story of my enrichment and research project with Largo.

Largo and me in the Nature Club House

Most of you reading this now probably met Largo when he was at work, maybe in the presence of my colleague Naturalist Betsy Mooney, who describes him this way:

“Largo is the calmest, gentlest, and most easy-going snake I've had the honor to work with. He is patient with children and adults, including those who are afraid of snakes, who left with a better understanding about snakes in general, or at least about Largo. He was my co-worker in the Nature Club House, and has fulfilled the Museum's vision of seeking to connect people to nature for the betterment of both. May he enjoy his retirement.”

Portrait of Largo with blue-appearing eyes—it happens as his skin loosens before a molt. Copyright 2024 Betsy Mooney

While you may think an ambassador animal would be something furrier, snakes like Largo are essential for reshaping how we perceive reptiles. Through encountering an approachable animal, guests have the opportunity to transform fear about snakes into curiosity. As Betsy noted, visitors who encountered Largo often left the Museum with a newfound respect for snakes and a better understanding of their ecological importance.

Pacific Gopher Snakes (Pituophis catenifer catenifer) are native to Southern California, where they inhabit meadows and fields—above and underground. In Santa Barbara, these snakes also use the burrows of animals like Botta’s Pocket Gophers (Thomomys bottae) as shelters. Pacific Gopher Snakes can be yellow to dark brown (or even red!) with rows of black, brown, and sometimes red spots along their bodies. Because they like to burrow, they have a protruding rostral scale on the tip of their snout, giving them a permanent, soft appearance of a smile. Unlike most snakes, they are active during the daytime, when they spend their time looking for food and basking in the sunshine.

A wild Pacific Gopher Snake spotted at a park in Cuyama

Gopher snakes feed on rodents, helping to regulate rodent populations and reduce the risk of diseases rodents transmit, such as hantavirus or Lyme disease. They find their food through scent, but not with their noses. The flicking of a snake's tongue is actually them smelling. They collect smelly molecules with their tongue, and once their tongue goes back into their mouths, it interacts with the Jacobson’s organ at the roof of their mouth that helps them understand their surroundings.

Largo demonstrates smelling with one’s tongue

The needs and abilities of gopher snakes inspired me to do a research project. Currently, there isn’t much research about reptiles and enrichment. However, there are a small number of studies demonstrating that when given the choice, snakes preferred a more enriched enclosure. Which shouldn’t be too surprising, right? If you were given the choice of a space with more variety—whether it be hiding places or seating options—it would probably be more appealing than a space with fewer options. However, it’s important to gather scientific data to support this concept robustly, to better inform the need for all animals—from snakes to sharks—to receive enrichment in human care.

I was interested in how I could create enrichment for Largo that mimicked the lifestyle of his wild counterparts. I created several new items inspired by Gopher snakes’ preference for places with high grasses, borrowed burrows, and their super smelling sense: a simulated gopher burrow, a plot of native grasses, and new, unfamiliar scents for Largo to explore. I observed Largo’s response to these new items to better understand the importance of enrichment for all animals.

Largo's enclosure always features some nooks and crannies, like this log shelter.

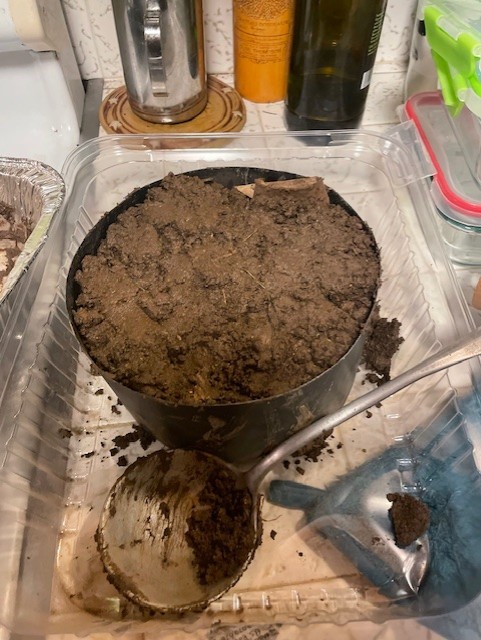

The burrow I created for my research was designed to mimic a gopher burrow, which is the gopher snake’s primary habitat. I gathered mud from gopher habitat near my home, a spot with a lot of gopher holes and gophers. But any new item added to an animal’s enclosure must be sanitized for their safety. How do you sanitize mud? I spoke with my professors, and it turns out most harmful microbes can be killed off by cranking up the heat. So I baked the mud at over 300 degrees Fahrenheit for three hours.

Artisanal slow-cooked mud in my kitchen

Then I shaped the mud in a way that resembled gopher tunnels—researching diagrams and observing the ones I saw in the wild. The process of making the tunnels was more difficult than I thought it would be—the gophers really have their work cut out for them! I used paper rolls and a plant pot liner to hold the shape of the tunnels and then I baked the burrow again so it would maintain its structure and remain sturdy for Largo.

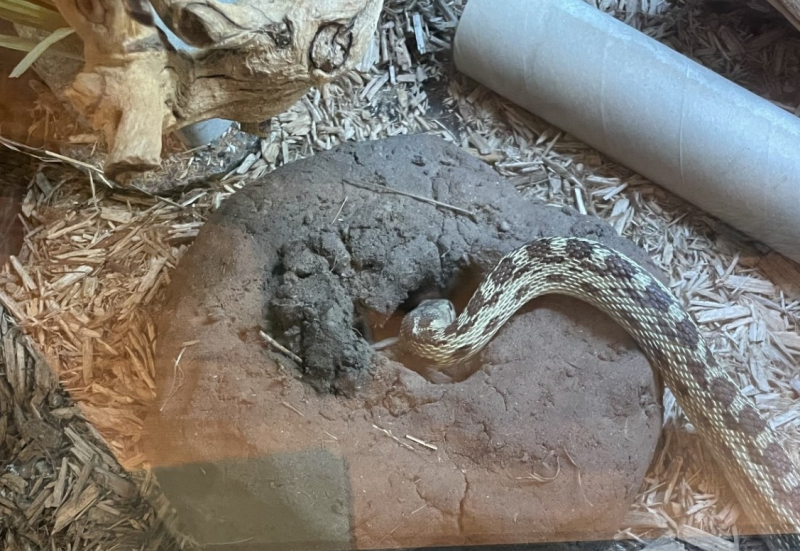

The completed burrow during a trial in Largo’s enclosure

I followed a similar selection and sanitation process with the native grasses for Largo—sourcing the grasses from the same place and also baking them. Creating the portable grass plot required a sturdy base made of cardboard. I discussed the process of gluing the grass to the cardboard with a reptile keeper friend of mine. He suggested a special non-toxic adhesive many keepers use in habitat construction.

To offer Largo unfamiliar scents, I wanted something to use as a base on which to apply the scent. I started with the cardboard rolls already used in Largo’s enclosure. The rolls are themselves a form of enrichment, providing different hiding spots and exercise options. I filled the tubes with paper towels dabbed with essential oils—such as pine or lavender—and sealed them from entry. I made sure the scent was not too overwhelming. I used some scents Largo would encounter in the wild, and other, completely new ones to expand his experience within his enclosure.

Largo explores the burrow during a trial. Sorry we didn’t have a snake-cam to show his POV!

The burrow, grass, and scent tubes were added to Largo’s enclosure separately and for fixed amounts of time as I recorded his responses. They were taken out once I was done gathering data. All items were added under my supervision and observation to ensure Largo was safe throughout. The data I collected to write a paper for my graduate program focused on the different behaviors Largo displayed in response to the enrichment I offered him. I observed that Largo was more active and demonstrated more behaviors in an enriched setting. My findings informed Largo’s care in that it widened the possibilities of what it means to provide snakes like him with enrichment and to think about what kinds of enrichment can fit best for the individual. I am going to see if I can give his next caretaker the burrow to use at home as part of an enrichment plan.

Largo’s enrichment also created educational opportunities. A benefit of doing this project in the Nature Club House was that it ended up providing space for guests to have conversations with me about snakes and enrichment. Not many people knew what enrichment was, let alone enrichment for snakes. I had several encounters with folks who were either scared or totally put off by snakes, but after I had conversations with them I could see the gears in people’s brains turn as their perspective of reptiles widened. Introducing them to the idea of enrichment meeting needs for exercise, stimulation, and variety elicited responses like: “Oh! They have needs, too! That makes sense.”

Even though my focus was the case study with Largo, these conversations were meaningful and felt relevant to the overall goal of my graduate projects. Just for my own curiosity, I took notes on the language used before and after my conversations with the public about my project. I made a word cloud at the end of my project from my notes and the word learned was the most used one. It was rewarding to reflect on how people left the Nature Club House having potentially learned something new about snakes. Even if they were still put off by snakes, people would tell me that after our conversations they saw snakes differently. Largo, with his soft “smile” and non-threatening presence, invited guests to observe his responses and gave us the space to share these ideas.

Observing Largo on the touch table with guests

Those of you who have recently visited may have noticed a sign or talked to an outdoor educator about how Largo is retiring. This species can live for a few decades in human care, and Largo likely has many good years ahead, but he is getting up there. He will have a wonderful home with a previous employee of the Museum who was one of his primary caregivers and can give him personalized one-on-one care. As they get older, snakes will become more stiff and have more trouble shedding their skin. Though they do not have external ears, they have an internal hearing system like we do, for processing sound through vibration rather than noise. Having some peace and quiet is nice for anyone as they get older, and it’s no secret that the Nature Club House can gather a lot of people and vibrations.

The welfare of all living things—out in the wild and in human care at places like the Museum and Sea Center—looks different from species to species. We are still learning so much about what it means to address the welfare of animals like snakes. It’s important to honor what we do know, which is why we determined that Largo retiring now would be the best decision for him.

Largo has also provided us with many molts for the touch table over the years.

As Largo enters his retirement, his legacy will live on in the countless lives he has touched. Largo served as an introduction to snakes for many, and motivated turning points in people’s attitudes—whether it be overcoming a fear or inspiring a passion. As we mark Largo’s retirement, we celebrate his contributions as an ambassador for his species. They inspire us to seek out new ways to encourage harmonious coexistence between humans and wildlife.

If you’re looking for more information on animal enrichment in human care, visit us at the Sea Center! At the time of writing, we usually host animal feeding presentations Saturday–Tuesday, often including conversation about enrichment. But whenever you visit, our staff is eager to share more about how we support our animal ambassadors, from sharks to the octopus.

Sources used in my research

Alba, A. C., Leighty, K. A., Pittman Courte, V. L., Grand, A. P., & Bettinger, T. L. (2017). A turtle cognition research demonstration enhances visitor engagement and keeper-animal relationships. Zoo Biology, 36(4), 243–249. NCBI.

Association of Zoos and Aquariums (2023). Animal Welfare Committee's Definition of Animal Welfare. AZA.org. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

Benn, A. L., McLelland, D. J., & Whittaker, A. L. (2019). A Review of Welfare Assessment Methods in Reptiles, and Preliminary Application of the Welfare Quality® Protocol to the Pygmy Blue-Tongue Skink, Tiliqua adelaidensis, Using Animal-Based Measures. Animals, 9(1), 1-22. MDPI.

Burghardt, G. M. (2013, August). Environmental enrichment and cognitive complexity in reptiles and amphibians: Concepts, review, and implications for captive populations. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 147(3-4), 286-298. Elsevier.

Decker, S., Lavery, J. M., & Mason, G. J. (2023). Don't use it? Don't lose it! Why active use is not required for stimuli, resources or “enrichments” to have welfare value. Zoo Biology, 42(4), 467–475. Wiley.

Hoehfurtner, T., Nagabaskaran, G., Wilkinson, A., & Burman, O. H.P. (2021). Does the provision of environmental enrichment affect the behavior and welfare of captive snakes? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 239(105324), 0168-1591. Science Direct.

Janovcová, M., Rádlová, S., Polák, J., Sedláˇcková, K., Peléšková, Š., Žampachová, B., Frynta, D., & Landová, E. (2019). Human Attitude toward Reptiles: A Relationship between Fear, Disgust, and Aesthetic Preferences. Animals, 9(5), 1-17. MDPI.

Lecointre, G., Raymond, M., & Miralles, A. (2019). Empathy and compassion toward other species decrease with evolutionary divergence time. Scientific Reports, 9(19555), 1-8. Nature Research.

Link, R. (2005). Living with Wildlife: Pocket Gophers. Living with Wildlife.

Marcellini, D. L., & Jenssen, T. A. (1988). Visitor Behavior in the National Zoo's Reptile House. Zoo Biology, 7(1), 329-338. Alan R. Liss.

Nafis, G. (2020). Pacific Gopher Snake - Pituophis catenifer catenifer. A Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

Myers, C., Myers, L.B., & Hudson, R. (2009). Science is not a spectator sport: Three principles from 15 years of Project Dragonfly. In R. Yager (Ed.), Inquiry: The key to exemplary science (pp. 29-40). NSTA Press.

Myers, C.A. (1997). The art and science of investigation: The webs we weave. Dragonfly Teacher’s Companion, May/June, 8.

Rose, P., Evans, C., Coffin, R., Miller, R., & Nash, S. (2014). Using student-centered research to evidence-base exhibition of reptiles and amphibians: three species-specific case studies. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, 2(1), 25-32. EAZA.

Santa Barbara Natives. (2023). Grasses and Grass-Like Plants. Santa Barbara Natives. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

Santa Barbara Zoo. (2023). Reptile Keeper.

Smithsonian National Zoo. (2023). Animal Enrichment. National Zoo. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

Spain, M. S., Fuller, G., & Allard, S. M. (2020). Effects of Habitat Modifications on Behavioral Indicators of Welfare for Madagascar Giant Hognose Snakes (Leioheterodon madagascariensis). Animal Behavior and Cognition, 7(1), 70-81. Animal Behavior Cognition.

Tuite, E. K., Moss, S. A., Phillips, C. J., & Ward, S. J. (2022). Why Are Enrichment Practices in Zoos Difficult to Implement Effectively? Animals (Basel), 12(5), 554.

Warwick, C., Arena, P., Lindley, S., Jessop, M., & Steedman, C. (2013). Assessing reptile welfare using behavioral criteria. Clinical Practice, 35(3), 123-131. In Practice.

Woodland Park Zoo. (2023). Empathy Initiative. Woodland Park Zoo. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

Young, A., Khalil, K. A., & Wharton, J. (2018). Empathy for Animals: A Review of the Existing Literature. Curator: The Museum Journal, 61(2), 327-343.

0 Comments

Post a Comment