A Chumash Basket Returns to Chumash Land

Are you sitting comfortably? We have a long story to tell you. It’s about something that happened this fall, but there are thousands of years of backstory.

In the late 1970s, some remarkable baskets turned up at an estate sale in San Antonio. Anthropologist Mardith K. Schuetz-Miller was in Texas working on her doctoral thesis when she saw them. She wasn’t a basket expert, but she sensed that these were special, perhaps rare California Indian baskets. The sellers knew nothing of their origin, but Schuetz-Miller followed her instinct and bought them.

Last year, Dr. Schuetz-Miller (now living in Northern California) reached out to SBMNH Curator of Anthropology John Johnson, Ph.D., whom she had known for many years. Dr. Johnson referred her to the Museum’s resident basketry expert, Curator Emeritus of Ethnography Jan Timbrook, Ph.D., for help in identifying the baskets’ origins. On seeing photos, Timbrook immediately recognized one as a beautiful Chumash tray, and asked if Schuetz-Miller might part with it. The answer was yes, and so this remarkable basket took another step on its long and winding journey back to Chumash land.

It was coming to join many other Chumash baskets gathered to the Museum by Timbrook. Basketry is her core area of expertise, along with the closely related topic of ethnobotany: the study of traditional plant knowledge. Timbrook has worked with the Museum’s basket collection for 47 years. The collection is substantial, preserving over a thousand baskets from Western North American Indian tribes. During her tenure, Timbrook has taken special care to grow the Chumash basket collection—a repository of this region’s long cultural heritage—from three baskets to 50. Not even the Smithsonian has that many Chumash baskets, which is as it should be: the Central Coast is their land of origin.

Timbrook has been adding Chumash baskets to Museum collections and exhibits for decades. Ventureño Chumash master weaver Candelaria Valenzuela wove the bowl pictured here, added to Chumash Life exhibits in January 2019.

A Brief History of a Long-lived Art

The current archaeological record shows basket fragments (and impressions of fragments) dating back nearly 5,000 years, but the local tradition of Native basketry probably goes back significantly further. Native people who were probably Chumash ancestors lived here at least 9,000 years ago. (Those familiar with Arlington Springs Man will know the record of human habitation in the region goes back even further, but is even harder to correlate with a particular culture group.) Suffice it to say that over thousands of years, Chumash basketweavers developed practices for making specialized baskets for every conceivable use: not just baskets for the gathering and storage of a whole range of dry goods, but asphaltum-sealed baskets for holding water, cooking baskets used to boil liquid with hot stones, and openwork baskets for fishing. Basically, if you lived here up until a couple hundred years ago, and you wanted to do something, you probably had a special basket to do it with. That basket was the result not only of highly skilled manual dexterity, but of a wider body of specialized knowledge, ranging from where and when to harvest the plant materials you had carefully managed, to the math a skilled basketweaver did in her head to produce elaborate decorative patterns without the aid of computers or graph paper.

Known as a "treasure basket," this elaborately woven basket jar was intended for holding small valuable items like shell bead money.

The cultural and environmental landscape that first produced these functional works of art is forever changed. On the Central Coast, visits by European explorers, the mission era, and the following periods of Mexican and American rule were the local manifestations of the imperialist cataclysm that shook the entire New World. Although our region largely avoided open warfare and brutal massacres, the introduction of Old World microbes decimated the Chumash population. The coercive imposition of European cultures and the seizure of Native land further devastated Chumash cultures.

The transformation of ecosystems has also been a key part of this devastation, as Anglo ways of using land turned environments sustainably managed by Native people for millennia into environments that could no longer sustain traditional ways of life. As M. Kat Anderson wrote in Tending the Wild—specifically mentioning the Juncus genus of rushes that supported the vast majority of Chumash basketry—

“The five million acres of wetlands that once existed in California have been reduced by 91 percent through diking, draining, and filling in for agriculture, housing, or other purposes. This puts a tremendous hardship on weavers who depend on plants such as rushes (Juncus spp.), sedges, and bulrushes (Schoenoplectus spp.) that are gathered from wetlands.”

Those words were printed 15 years ago, and the situation is hardly better today, with our state’s tiny sliver of remaining wetlands now under pressure from rising seas.

Rushes in the genus Juncus are important materials in Chumash basketry. Plants like these would have been more abundant before local wetlands were drained and developed. It’s a challenge for modern weavers to sustain these plant sources now that Juncus plants are few and far between.

Chumash basketweavers persisted in the face of these overwhelming pressures on their culture and the environment of their homeland. During the mission period, weavers continued to create baskets in a wholly traditional style but were also commissioned by Spanish authorities to produce specially-designed works. Juana Basilia Sitmelelene’s astounding presentation basket—which welcomes guests to Chumash Life at the Museum—is one of these.

This basket by Juana Basilia Sitmelelene (1783?–1838) incorporates heraldic designs from Spanish colonial coins and an elaborate inscription that documents its having been made during the period of Pablo Vicente de Solá, the last Spanish governor of California, between 1815 and 1822. This is one of only seven such baskets known to exist, most or all apparently made by Chumash weavers at Mission San Buenaventura.

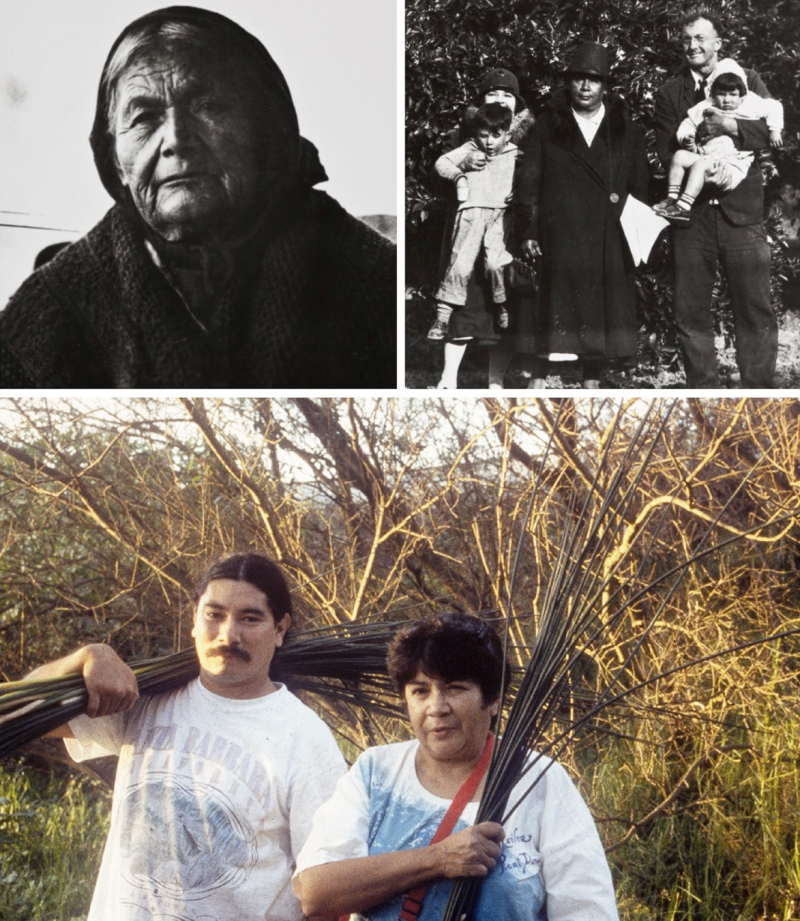

Ventureño Chumash basket weavers Petra Pico (1834–1902), Donaciana Salazar (1836–1905), and Candelaria Valenzuela (1847?–1915). Cassidy Family Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

When the newly independent nation of Mexico gained control of Alta California and the government took over the missions in the mid-1830s, mission lands were divided up for ownership by wealthy and powerful citizens, and many people in the much-diminished Chumash population sought work on far-flung ranches. People with important cultural knowledge were isolated by this dispersal, although some—like the historic community of basketweavers pictured above—remained close-knit by family ties. Of these, Candelaria Valenzuela was “the last of the old-time Chumash weavers,” Timbrook recounts. “She died in 1915.” But the seeds of her art did not die with her. They lay dormant, preserved in two forms: baskets and plant knowledge.

A Family Legacy of Culture

Generations of Chumash people have passed down their cultural knowledge within their own families and beyond. Famously, the prolific anthropologist J.P. Harrington recorded an astounding amount of cultural knowledge relayed by the Chumash consultants with whom he worked. The legacy of that consultancy is very personal for Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto (Barbareño Chumash), a longtime member of the Museum’s California Indian Advisory Council. Ygnacio-De Soto’s mother Mary J. Yee, grandmother Lucrecia Ygnacio Garcia, and great-grandmother Luisa Ygnacio all worked as consultants on Chumash language and culture to Harrington.

Five generations of Chumash plant knowledge in three photos. Clockwise from top left: 1) Luisa Ygnacio (1835?–1922), 1913. Courtesy of Josephine Robles and John Yee, SBMNH collection. 2) Mary J. Yee (née Rowe) holding her son John Yee, Lucrecia García (née Ygnacio), John P. Harrington holding Mary’s daughter Angela Yee, 1931. Harrington collection, SBMNH. 3) Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto and her son Gilbert Unzueta, gathering Juncus.

Harrington’s notes on the knowledge passed down by Ygnacio-De Soto’s forebears and his other Chumash consultants—notably the aforementioned basketweaver Candelaria Valenzuela and Fernando Librado Kitsepawit—provided a scholarly foundation for cultural revival. Yet this information—preserved in thousands of pages reproduced on microfilm and held at many institutions, including the Smithsonian and SBMNH—is not readily accessible. While scans of many microfilmed pages of Harrington’s notes are available online through the Smithsonian, Harrington’s inscrutable handwriting, the multi-lingual nature of the material, and the freeform nature of his consultations make the notes difficult to decipher. This is an ongoing task that will keep scholars busy for decades; Harrington worked with people from many culture groups during his long and prolific career, and their descendants will be interpreting the results for a long time. Ygnacio-De Soto’s nephew James Yee is one: as a linguistics graduate student at UCSB, he is studying notes on the Barbareño Chumash language made by his grandmother Mary Yee, who kept notebooks recording and commenting on her work with Harrington.

Timbrook drew on the same sources in research for her 2007 book Chumash Ethnobotany: Plant Knowledge Among the Chumash People of Southern California. Chumash ethnobotany has a living presence at the Museum in the form of the Sukinanik’oy Garden of Chumash Plants, which offers guests a taste—not literally, as some plants are toxic—of the plant knowledge at the heart of every aspect of traditional Chumash life.

The Sukinanik’oy Garden of Chumash Plants looking refreshed after late winter rains.

Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto worked on the team that created the garden and has been both a preserver and a beneficiary of the legacy of knowledge it embodies. She and her family selected the name Sukinanik’oy, the Barbareño Chumash word for “bringing back to life.”

The family’s work with Harrington has been “a long history without any break,” she recalls. She has childhood memories of Harrington’s constant presence at her family home: “He was always with my family when he was here. J.P. Harrington worked with my great-grandmother Luisa for 50 years, off and on, and her daughter Lucrecia, which is my grandma, and then my mother Mary Yee. Three generations.” During that time, “he became a family member.” Mary Yee met him when she was a girl of 16, and they worked together many years. Yee wound up nursing Harrington as he slid into late-stage Parkinson’s disease at life’s end.

Concerning herself, Ygnacio-De Soto remembers being “a pain in the butt” to Harrington. “I was always bugging him when he was trying to work with my mother,” she recalls with a wry smile. Her childhood lack of awe for the now-famous linguist is unsurprising: she has no patience for inflated egos. For his part, Harrington seems to have had an unassuming quality that made him a successful confidant. She recalls that part of his skill was this unpretentious approach. “He didn’t lord it over you. That’s one thing with any Indian, I think,” says Ygnacio-De Soto. “If you present yourself as self-entitled, you’re not going to get anywhere with us.” Harrington “just blended in with everyone,” she remembers.

Ygnacio-De Soto has visited the Sukinanik’oy Garden regularly as part of a basketweaving group that has been meeting on the Museum campus for several decades. The group was seeded by California Arts Council artist-in-residence Patricia Anna Campbell in the 1980s, who visited the Museum to study Chumash baskets. “She got all the Chumash together here doing projects, and that was one of them,” Ygnacio-De Soto recalls. At the time, Ygnacio-De Soto was busy working as a registered nurse. “I did everything except deliver babies and assist surgery, and I was raising a grandson. So I was up at five in the morning, at the hospital at six . . . I was always in my own little world,” before Campbell “got me out of myself,” she remembers. “Then I started sharing my family stories here.”

Ygnacio-De Soto reads stories handed down in her family during Chumash Culture Day, a public program at the Museum in 1990.

Ygnacio-De Soto and Timbrook both first learned to weave from Campbell at that time, based on reverse-engineering of Chumash techniques from baskets Campbell studied in the Museum’s collection. Decades later, the three women are still weaving at the Museum, accompanied by several other patient practitioners of this rewarding but time-intensive art.

The basketweaving group in the Sukinanik’oy Garden in fall, when outdoor exhibits were open at the Museum.

Ygnacio-De Soto readily acknowledges the difficulty: even after all these years of practice, she says, “I’m not a weaver, I’m an admirer and a groupie.” Weaving is “not an easy job. But for the Chumash, you had to [have these skills]. This was your daily living. Before you had all this fancy dancy Tupperware stuff, this was it. And if you were in a hurry and needed to have something right away, you just throw together something ugly like this,” she says of her current project. “Holes, different sized stitches, broken stitches, split stitches, it’s terrible. I don’t have the gift, but I still love it.” In her experience, the practice of weaving—even if you aren’t a master weaver—can be relaxing, even therapeutic. She puts this in terms you’d expect from a retired nurse: the time spent concentrating on a practice like this has the therapeutic value of “a bottle of Ativan or Valium.” Without the side effects, of course.

Portrait of a basket “groupie”: Barbareño Chumash elder Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto.

Since the formation of their basketweaving group with Campbell, Ygnacio-De Soto and Timbrook have since learned from many other teachers, including Diegueño weaver and collector Justin Farmer, master weaver Abe Sanchez (whose Indigenous ancestry is from the Purépecha in Mexico), and Navajo weaver Dolly Soulé. The California Indian Basketweavers Association (CIBA) has been an essential support in sharing inspiration and knowledge among weavers, including all these. Sanchez has wide expertise and has worked with many Native groups, teaching weavers how to make baskets in their own traditions. “He’s made some fabulous baskets,” says Timbrook. “He’s a great teacher, very patient, but always tells you when you’re doing it wrong.” She’s wearing a mask when she tells me this, but I can hear the smile in her voice.

A Guest of Honor in the Sukinanik’oy Garden

This firsthand experience of basketweaving and the knowledge of how it has been practiced across many Native cultures has given Timbrook, Ygnacio-De Soto, and other active members of the basketry group a “really good sense of what goes into producing a basket,” says Timbrook. That background helps them appreciate why a basket like the new Chumash tray Schuetz-Miller found in San Antonio “is just awesome,” in Timbrook’s words.

Detail of the new tray. The date and weaver are unknown, but it is characteristically Chumash. Whoever she was, the basket’s creator “was a really skilled weaver,” says Timbrook. “To be able to keep track of all those complex designs, it’s quite an accomplishment.”

The pandemic stalled the new basket’s arrival at the Museum. Schuetz-Miller was understandably reluctant to ship it through conventional channels, and the Museum’s trusted art shipper couldn’t travel up as far as her home in Northern California. The basket wound up getting special chauffeur service from the Museum’s new Associate Curator of Anthropology Brian Barbier, M.A. Barbier and his wife Ashley picked up the basket on a detour from a late summer camping trip at the height of Northern California’s devastating fires. On their way, they drove under the surreal, sharp-edged shadow of an apocalyptic smoke cloud on the Humboldt Coast, and after picking up the basket, were chased away from the region by a towering pillar of smoke blowing off of the Oroville foothills. The precious basket—encased in a customized padded box—“rode on a memory foam mattress all the way back to Santa Barbara,” says Barbier. He was happy to be its chauffeur, having loved California Indian baskets since he was a young community college student, learning twined basketweaving styles and plant knowledge from friends and teachers with Hupa, Pomo, Miwok, and Maidu heritage and expertise.

On a cool fall day in 2020, the new basket visited our Sukinanik’oy Garden, a guest of honor to the basketweaving group. It had traveled well over 2,000 miles on its journey from San Antonio, to Northern California, to Santa Barbara. Its arrival in its land of origin was much anticipated by Ygnacio-De Soto, and the basket lived up to the hype. “It’s the most beautiful basket that I’ve ever seen,” she said.

Ygnacio-De Soto and the new basket at a physically distanced private meeting of the basketweaving group in fall 2020, when Museum operations were permitted outdoors.

“The most beautiful basket that I’ve ever seen” is not idle praise from Ygnacio-De Soto. She’s been appreciating the works of master weavers at CIBA annual meetings and in museum collections for decades. “Whoever wove that basket was a master weaver,” she says. “It takes your breath away. I don’t have much of that, but anyhow,” she jokes. “Now my niece, I wish she was here.” Ygnacio-De Soto’s niece Samantha Sandoval now lives in Sacramento, but learned to weave in the Chumash style in 2012. “She has the gift. She can weave intricately. I’m looking forward to her creating something like that.” No pressure, Sam!

Sandoval—who has also served on our advisory council—was able to visit the Museum later in fall and see the basket for herself. Though modest about her own patient and precise work, she has a deep appreciation for the personal investment that goes into masterpieces of basketry. “It’s awesome to see beautiful baskets, how much time went into them,” she says. “When you make a basket and learn how to do this, that’s when you really appreciate a Chumash basket, or even any basket,” she says. “Because it took a lot of time for that person to make that basket. Whatever they wanted to show, whatever their story or how their life was, their experiences, it comes out in your basket.”

Sandoval working on the base of a shallow bowl basket. The different colors are achieved by different parts and treatments of the same kind of Juncus.

The time-intensive process starts with gathering plants. Sandoval’s weaving has stalled in Sacramento, in part because she is separated from her weaving community, and in part due to the difficulty of plant access. “I don’t have access to Juncus up there. It doesn’t just grow everywhere.” In the Santa Barbara area, “I gather Juncus myself,” she says. “I’ve gathered it at Maria Ygnacio Creek, which is named after my great-great-great-great-grandmother.” It’s her practice to get a property owner’s consent when gathering on private property. She’s also worked to transplant some wild plants to more accessible areas, but gophers and drought have worked against her efforts. Still, she has some Juncus gathering spots in Goleta.

Juncus stems are pulled up, not cut, and left whole while they are allowed to dry. After months, they turn a light straw-tan color. Only after they’re dry does the weaver split them into strands that can either be dyed or used in their natural color. Natural variation results in reddish-brown bases that help Chumash weavers achieve the polychrome (multicolor) effects for which they are famous. “I found a plant that grows a lot of good brown roots,” Sandoval says with satisfaction. Weavers get dark colors by dyeing their Juncus strips, too. “That’s a whole process right there,” Sandoval says. “To prepare the dye, you have to search for the oak galls or black walnuts or rusty nails,” which provide the pigment when mixed with water. (The iron from rusty nails interacts with the tannin from oak galls or walnut shells and helps to set the black color.) “After it’s been so many weeks, sitting, then you can add your Juncus, and that takes several weeks to a couple months to dye.”

Even if the weaver isn’t trying to achieve a special color, they still have to painstakingly remove the pith from each strip with a sharp tool. A razor will do; if you’re a purist you might use a sharp piece of shell. Then the weaver trims the de-pithed strips to a uniform width. Finally, to make them pliable for weaving, the strips have to be soaked, “for just the right amount of time. If you oversoak it, that’s not good, and if you undersoak it, it can break easily. It all takes time.”

Time is in short supply for Sandoval in her life as a full-time nurse, but she loves the practice of weaving.

“I love it in the morning on a weekend, because when I first wake up, my mind is clear, I’m wide awake, and I feel more relaxed. I can’t do it if I come off of work and I have a lot on my mind. My job can be stressful some days, so I don’t basketweave after work. When your mind’s clear, you feel like you can create. I feel like I’m starting new, you know? I feel like I’m putting more love into my basket.”

“It looks perfect,” Sandoval says of the new tray. “I just wish I can do that, that I can be that skillful.”

Somebody put a lot of love into the new tray. Because no data came with it via the San Antonio estate sale, we can only conjecture at how it got there. As San Antonio is near historic Fort Sam Houston, Schuetz-Miller supposes that an officer at the fort may have made trips out west and brought the basket back, perhaps passing it down in his family. That’s certainly possible, but we don’t know one way or another. What we can be very confident about is the fact that the somebody who put so much love into it was a Chumash woman. We know this in part because 55 years ago, two anthropologists who were totally fascinated by Chumash baskets set out to describe what makes a classic Chumash basket.

What Makes a Chumash Basket?

Every Chumash basket has a story to tell about the person who produced it, and the world in which she lived. In 1965, Lawrence Dawson, Senior Museum Scientist at UC Berkeley’s Lowie (now Phoebe A. Hearst) Museum, and UC Santa Barbara Professor of Anthropology James Deetz published their efforts to discern the technical side of those stories. “A Corpus of Chumash Basketry” took a detailed look at 85 baskets, most of which were from nine museums. Dawson and Deetz sought to outline the commonalities in the materials, forms, and designs of baskets documented as Chumash, and in doing so describe what was technically remarkable and distinctive to Chumash basketry. They came up with some of the design and technical characteristics that allowed Timbrook to recognize the estate-sale find as a classic Chumash tray.

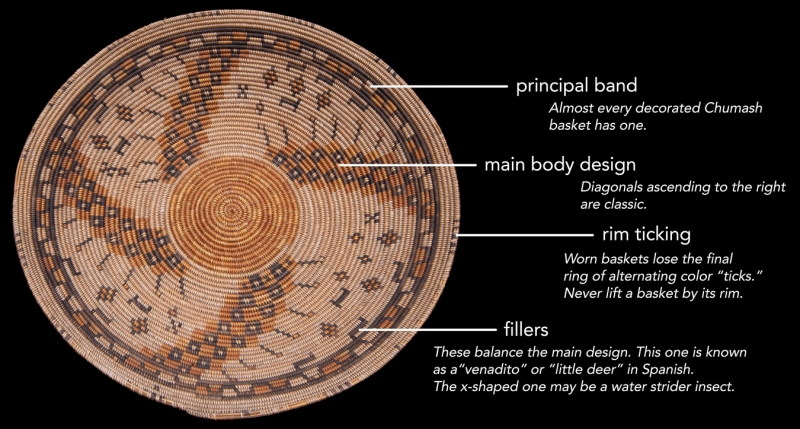

These are some design characteristics of the new tray which help identify it as Chumash.

“It has all the characteristics of Chumash design,” says Timbrook. “It has the principal band, the main body’s own design, the fillers, the rim-ticking.” She points out the fillers, patterns known for convenience as venaditos, water striders, and so on. The Chumash names and traditional meanings of these images are unknown, and we can’t assume that what looks to us like a little deer or an insect really is one, or represents something else. When it comes to the plant materials, however, we’re on firmer ground. “The materials are perfect for Chumash,” says Timbrook. “It’s a three-rod Juncus foundation sewn with split, peeled stems of sumac, natural orange Juncus, and dyed black Juncus. It’s an absolute classic Chumash basket.”

Coiled foundation? Sewing strands? What are these? A lot of us think of basket-weaving and immediately picture weaving strands in and out of a pre-built armature that looks like an asterisk, with stiff sticks protruding in all directions from the center. Most Chumash baskets are constructed by coiling instead. They’re built more like a snail’s shell than a spider’s web; the weaver progressively grows a small disc into a large, three-dimensional structure.

This basket “start”—the beginning of a basket in process—in our Chumash Life exhibits illustrates how coiled baskets are made of foundation and sewing materials, which can be different. The foundation is made of whole Juncus stems (sticking up and to the right). The sewing strand (wrapping around the foundation) is split Juncus. The dark brown and tan are natural colors of Juncus, the black is dyed Juncus, and the bright white is sumac. The basket is a replica, but the bone awl is an artifact. Asphaltum on the end made it more comfortable to use.

Whole stems of Deergrass or slender Juncus rush form the foundation coil, and split material forms the sewing strands, which the weaver uses to enclose the coil foundation and sew it to the previous row, poking holes in the material with an awl. The awl is traditionally made of bone for Chumash weavers, though many modern weavers use awls with metal points. “It’s important to have a good awl,” says Sandoval. “If it’s not the right size, it could break your weave or cause some damage. You’ve gotta make sure you put the awl in the right spot” to avoid splitting stitches. In the finest coiled Chumash baskets, the stitches are so densely woven that they almost totally obscure the foundation. Some baskets have as many as 20 stitches per linear inch. Other distinctive details include the rightward weaving direction, the manner of splicing in a new sewing strand, and how the rim row is finished.

Ethnology and the Museum

As a culturally valuable artifact that we hope to preserve for many generations, the new basket will be stored in our collections, safe from pests, UV and visible light, rough handling, and changes of temperature and humidity. It certainly won’t be visiting the garden every day, much as it may have an affinity for the people and plants of that place. Yet the fact that it was getting out to meet people wasn’t all that surprising. Although most items in museum collections (and not on exhibit) are accessible only to researchers, ethnology—the subset of anthropology devoted to living cultures—is necessarily different. All museum work is stewardship; all stewardship is a balancing act between access and preservation. As a steward, your goal is to share something in a way that can be sustained for generations. In ethnology, what you’re sharing has deeply personal significance for living people. “When I see those baskets,” Sandoval says, “it makes me feel really good. It’s a wonderful feeling to know that those baskets were made by my ancestors, and that somebody really took care of it, respected the basket, and what-all goes into it.”

In zoology and earth science, curators facilitating access to collections primarily check the research credentials of their visitors. Ethnology has to be different. “I always have the policy of inviting Native people to come and see things from their own culture area,” Timbrook explains. “Native people from all over have shared a lot of information with us, too. Many Native people have told me that the baskets and other artifacts in the Museum are like family members: they’re alive, and they need human contact. We have to respect that.” The exchange of information between museums and Native artists is mutually beneficial. Museum collections can support the continuance of traditional arts. Many such collections were started by Anglos in order to preserve “dying” Native arts for posterity. Today the situation is reversed: living Native arts are giving old museum collections a compelling reason to exist and grow.

“For a long time, people who collected baskets didn’t think it was important to record the maker’s name,” recounts Timbrook. “It’s a real shame that so many artistically and technically skilled weavers historically remained anonymous. Today, the Museum seeks to acquire baskets by contemporary Native people and honor them for their work.”

Santa Ynez Chumash weavers visiting the Museum in 2018. Left to right: Alyssa Arguilles, Lisa Valencia, Kristina Talaugon-Rivera, basketweaving teacher Abe Sanchez (Purépecha), Carmen Sandoval, Angelina Hernandez, Elise Tripp, Sally Hammel, Mercy Weller, Susie Hammel-Sawyer, and Timbrook.

The art of Chumash basketweaving is growing again, notably among the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. “When the new Chumash museum opens over in Santa Ynez in a year or so, people will be blown away,” Timbrook anticipates. “Basketry is undergoing a tremendous revitalization, and there are some excellent weavers over on the Santa Ynez Reservation now. So hopefully we’ll be seeing things like this”—she holds up the new tray—“more in public.”

Meanwhile, Timbrook hopes the new tray might appear in an upcoming Maximus Gallery exhibit here at the Museum featuring rarely-seen curatorial favorites from the Collections and Research Center. Timbrook will advocate for the tray’s inclusion, although she’s technically now a curator emeritus. She retired in the spring of 2019 after 45 years of paid tenure at the Museum. But you don’t walk away from traditions and relationships like hers. Soon after her retirement party, she was back at work in her old office, and back at work in the garden.

During the pandemic, Timbrook has been in the garden as much as she’s been allowed.

In winter 2019, Timbrook and Ygnacio-De Soto both worked at the Folk & Tribal Arts Marketplace. For some 20 years, Timbrook has run the Out of the Closet booth, so named because it features forgotten treasures from closets around town. Before the sale, community members donate folk art and global crafts in need of new homes. Timbrook assesses them, prices them to sell, and they usually go like hotcakes. The money raised goes towards the Department of Anthropology’s modest acquisitions fund. The department avoids buying items of great antiquity, because purchasing archaeological artifacts can encourage looting of culturally significant sites. More commonly, the funds are used to buy the works of living master weavers or items which are historic rather than ancient. Out of the Closet funded the purchase of the new tray. So how old is it?

“People always want to know how old baskets are,” says Timbrook. “The typical thing is to say that if it has all these fancy designs on it, it must be ‘early,’ maybe even early nineteenth-century.” Timbrook doesn’t hold with those assumptions. “You can’t tell that for sure,” because the complexity of the design varies with the weaver’s skill and the basket’s purpose. However, her wild guess—informed by decades of working with baskets—is that it may be from about 1800–1825. “It’s really hard to say. But it’s in perfect condition, almost. It has just a few little broken stitches around the rim, much better condition than most Chumash baskets that we’ve seen come out of private collections.” Old as it is, this beautiful basket feels as alive as the plants from which it was created, which—perhaps 200 years ago—would have stood dense and green at the margins of local wetlands.

“I just love the plant,” Sandoval had told me, speaking of Juncus. “It’s amazing how you can make a basket from this plant.” Her words came home to me when I ran across a bunch of Juncus in my neighborhood. It was like meeting a celebrity you’ve only heard other people talk about. Thinking this might be a weaver’s patch, I tugged just one rush from the ground. I split it with my thumbnail and took the strips home in my pocket, where they dried and crinkled. I soaked them and they became elegant and pliable. The strength of the fibers was astonishing. I let them dry again, and they weakened slightly. I gave them water, and their strength returned. I think of myself as a person with a scientific outlook, and personally, I don’t like to project human attitudes onto the rest of the natural world. But frankly, the best way I can describe a strip of Juncus is to say that it feels like something that wants to be a basket.

We Persevere

“I know that the plant is alive, prayers go into those baskets, those baskets have stories. They have a life of their own,” says Eleanor Fishburn née Arellanes. Although music—not weaving—is her strength, Fishburn understands the meaning of a basket. “Basketry is something I’m really just starting to get involved in. I’ve been busy raising kids, raising grandkids.” Fishburn is the current chairwoman of the Barbareño Band of Chumash Indians, and has served on the Museum’s advisory council for about a decade.

Fishburn sings as she gathers Dogbane to prepare regalia.

In her family, music has been the most important way to sustain Chumash culture and support the human spirit. “I love singing and dancing. There’s something that goes on when you get your regalia [ceremonial clothing] together, and you put it on, and it just moves that spirit inside of you, and your feet are touching the ground, and your voice is carrying up to the sky.” It’s a feeling of connection that gives her chills (the good kind).

On the fall day Fishburn visited the Sukinanik’oy garden, she harvested Dogbane for use in regalia. She loves “the whole ritual of the gathering, the preparation of the plant,” and the feeling of connection it inspires. “I love the way it brings us together as a community. We sit around and we talk good medicines, and that’s where I’m at today.”

Although I’ve left her words for the end of this story, Fishburn was the first to arrive on the first day the new tray came to the garden. Before she got to work gathering plants, she cradled it in her clean hands, and her glasses fogged up. She was the first Chumash person to hold it on its return to Chumash land.

“Sometimes the path that we walk is not easy as Indigenous people,” says Fishburn. “We get pulls from this way and that way and all kinds of ways. Today that basket, and this opportunity, meant healing to me. It meant that it may not be easy, but I’m right where I need to be. Sometimes we gotta walk through the fire to come out better and understanding, and maybe more empathetic and caring. I try just to keep positive, and that basket, it just took me back to the spirit, took me back grounded. I’m where I need to be, and this is who I’m doing it for, the ancestors, and for my grandchildren, for the future generations. The basket is beautiful. It’s a blessing that those baskets are still alive. As Chumash, we do persevere. We are persevering."

Fishburn and the new basket in the Sukinanik’oy Garden

Bibliography / Further Reading

M. Kat Anderson, Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).*†

T. Braje, J. Erlandson, and J. Timbrook, 2005. “An Asphaltum Coiled Basketry Impression from San Miguel Island.” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 25(2): 61–67.*

Kaitlin M. Brown, Jan Timbrook, and Dana N. Bardolph, 2018. “‘A Song of Resilience’: Exploring Communities of Practice in Chumash Basket Weaving in Southern California.” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 38(2): 143–162.*

Lawrence Dawson and James Deetz, “A Corpus of Chumash Basketry,” UCLA Department of Anthropology Archaeological Survey Annual Report, vol. 7 (1965): 193–276.*

Jan Timbrook, Chumash Ethnobotany: Plant Knowledge Among the Chumash People of Southern California (Santa Barbara and Berkeley: SBMNH and Heyday Books, 2007).

Jan Timbrook, Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto, John R. Johnson, and Nicolasa I. Sandoval, “Juana Basilia Sitmelelene (Chumash, 1782–1838) coin basket,” Infinity of Nations: Art and History in the Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian. Accessed April 9, 2021.

Jan Timbrook, 2014. “Six Chumash Presentation Baskets.” American Indian Art Magazine 39(3): 50–57.

* Available in the Museum Library. Contact terri@sbnature2.org to plan your visit.

† Available in the Museum Store. Contact kzsembik@sbnature2.org or check sbnature.org/store for details.

7 Comments

Post a CommentA beautifully written article on a beautiful basket, a precious heritage, and its ongoing life! It has been a deep joy and privilege to work with this basketry, with Jan, Ernestine, Juanita Centeno, Karen Osland and other basket makers through the years, and to see this continue today. Thanks to the Museum for sponsoring the original research with the Chumash Basket Project and the regional Chumash Culture Youth Project back in the eighties, and for providing an ongoing home for our Chumash basketry circles and other cultural activities. It has truly been kamulayatset (a beginning which will always be.) Thank you, Jan!

In recognition of Jan Timbrook's tireless work in obtaining and researching the outstanding baskets in the Museum's collection, this magnificent basket has been welcomed home by the hands of today's Chumash basketweavers. Cheers!

Beautifully written story by Owen. Thank you for sharing.

Any known baskets found in the Big Sur area? Recently found my roots in the Chumas and Costanoan lineage. Now called Olone ancestry.

Hi Lurando, Big Sur is indeed in historic Esselen territory, which extended from Point Sur across the Santa Lucia Mountains into the Salinas Valley. They formerly occupied a much larger area extending from the San Francisco Bay to Monterey County until about 3000 years ago. Around that time Ohlone populations expanded into the Peninsula region and down to Monterey Bay. The Esselen influenced language, culture, and basketry of several neighboring people including the Ohlone and Salinan. Archaeological fragments of Esselen basketry were found in Isabella Meadows Cave in Monterey County. They made cooking baskets, conical burden baskets, mortar hoppers, water bottles and winnowers, all in the twined weaving technique. The Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum at UC Berkeley and the Monterey County Historical Society collections include examples of archaeological Esselen basketry, but no documented ethnographic examples survive. Ohlone basketry is much better-known than Esselen, as there are many examples in museum collections. Ohlone made twined baskets, including an unusual type of winnower called a walaheen, and also coiled baskets that were sometimes ornamented with shell beads sewn into the weaving in geometric patterns. Ohlone baskets are preserved in collections at the Smithsonian, Peabody Museum Harvard, American Museum of Natural History, British Museum, Musee de l’Homme Paris, Autry Museum in Los Angeles, and other institutions in California and elsewhere. There is a well-known contemporary Ohlone weaver, Linda Yamane, who has revived knowledge of walaheen weaving and also makes spectacular coiled baskets covered with feathers and shell beads in the tradition of her ancestors. Here at SBMNH we have a walaheen made by Linda Yamane, but no older Ohlone or Esselen baskets. The best reference for information and photos of Esselen and Ohlone basketry is Indian Baskets of Central California: Art, Culture, and History, by Ralph Shanks and Lisa Woo Shanks, Costaño Books, Novato CA, 2006. Distributed by University of Washington Press (if it’s still in print).

Haku, I'm so grateful to have come across this article, I have a great desire to learn how to make a traditional Chumash basket. And Eleanor is my relation such a proud moment to see my family in this article. If anyone could please get me in contact with Samantha Sandoval, I would greatly appreciate it. I would love to be one of her students, and I too live up north, just 45 mins from Sacramento. much love and appreciation for this article. Many thank you's

Haku Mary! I told this story hoping we could bring more people together around this beautiful artistic tradition, so your comment fills me with joy. Please write to me at info@sbnature2.org and I'll forward your email to Samantha.