Grandpa’s Museum: Third-Generation Bird Returns to the Nest

The events described in this story took place before our new era of social distancing.

After more than a hundred years, we’re sort of used to people taking a family interest in the Museum. Generations of Santa Barbarans (Barbarians, depending on whom you ask) have enjoyed pushing the button on our electrified rattlesnake, peering into our dioramas, and exploring for wildlife on the shady banks of Mission Creek. Longtime Museum and Sea Center supporter Natalie Myerson—whose late husband Raymond served as a trustee and the Museum’s treasurer for over 25 years—loves to tell the story of how her grandchildren grew up calling this place “grandpa’s museum” (and we love to hear it). We suspect there are other families out there who feel a similar connection, based in their own tradition of service. Recently, we enjoyed a special visit from a guest who has a very literal claim to call us “grandpa’s museum”: Keith Dawson, grandson of Museum founder William Leon Dawson.

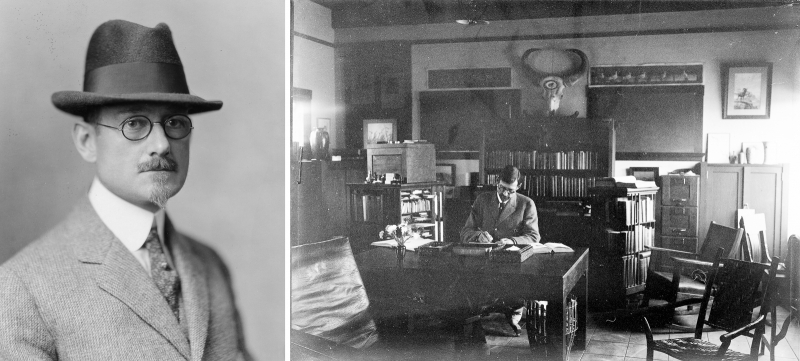

W.L. Dawson. At right, pictured hard at work in his home study c. 1910

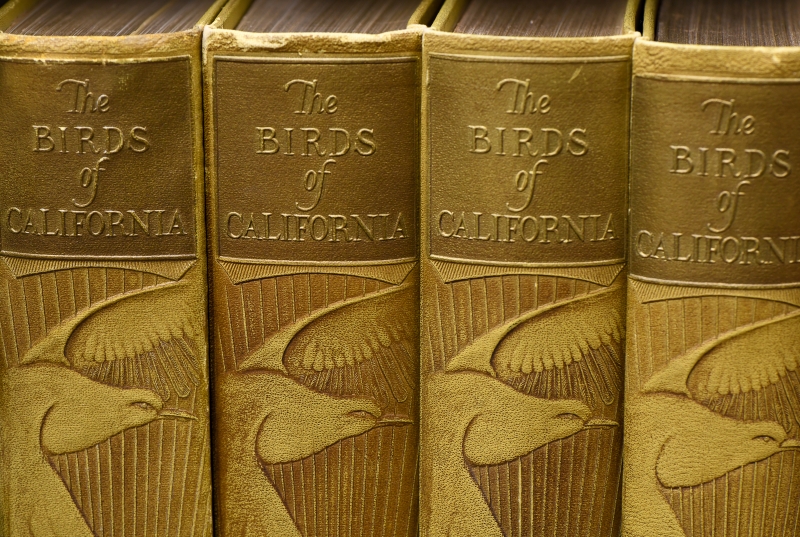

W.L. Dawson was a Midwestern divinity-student-turned-ornithologist for whom the study of birds was not just a career, but a calling. His passion for the subject is clear in the documents he left behind, including the extensive multi-volume books he published on Birds of Ohio, Birds of Washington, and Birds of California. If his life had not been cut short at the age of 55 by influenza that worsened into pneumonia in 1928, he would have gone on to publish Birds of Mexico and perhaps more.

Volumes of Dawson’s Birds of California in the Museum Library’s rare book room

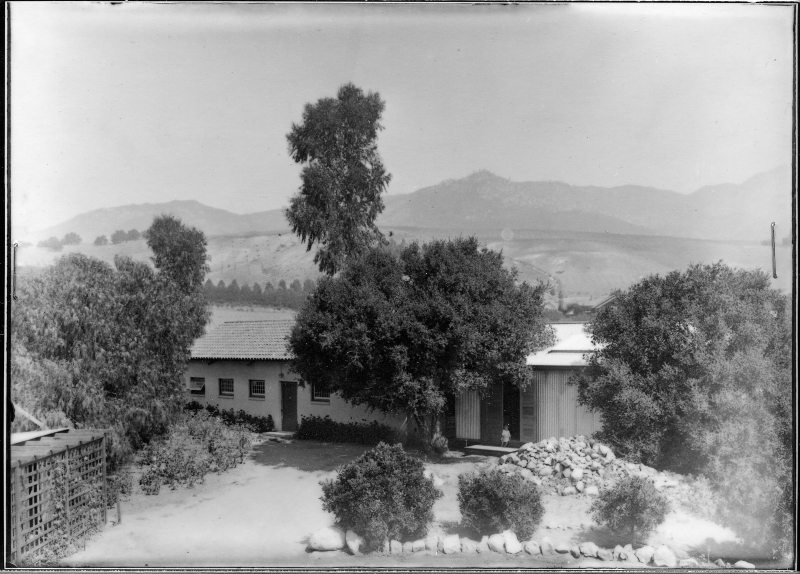

Dawson laid the egg for what would become SBMNH when he founded the Museum of Comparative Oology in 1916. Dawson’s home—and the original base for his collection and the nascent Museum of Comparative Oology—was located at “Los Colibris” (Spanish for the hummingbirds) on Puesta del Sol, right around the corner from our campus today. The area where Dawson kept his specimens was reinforced against theft and disaster and was affectionately known as the Iron Nest. Ornithologists and hobbyists from far and wide visited Dawson’s home to examine his extensive collection. In SBMNH lore, his wife Frances Etta Dawson is credited with the idea to start a real museum, perhaps in part because she was fed up with hosting all the visitors who came to look at W.L.’s collection when it was located in their home.

In this photo of Los Colibris from the 1910s, you can see La Cumbre Peak, center background. Notice how the hills in the midground—now developed as the Mission Canyon neighborhood—are fairly bare at this time.

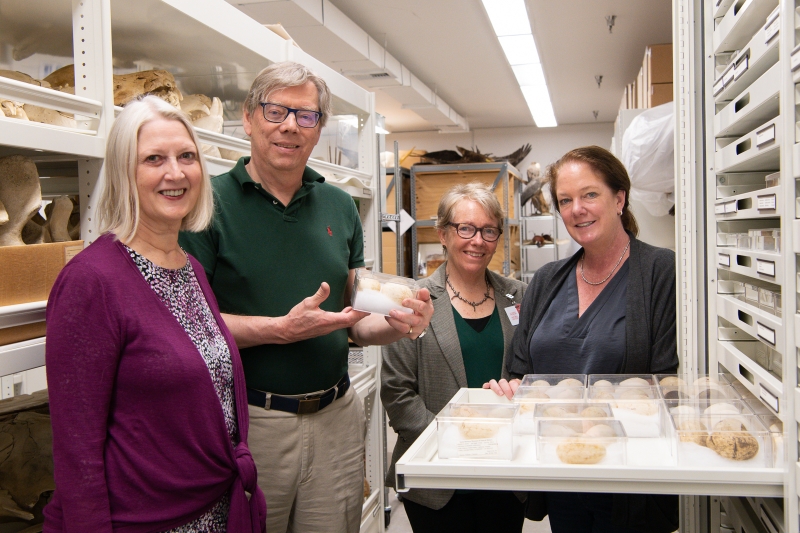

Naturally, grandson Keith and his wife Katharyn received a special tour when they visited the Museum in early 2020 to examine Dawson’s legacy here. Curator of Vertebrate Zoology Krista Fahy, Ph.D., gave them a behind-the-scenes look at birds, eggs, and nests in our Collections & Research Center, and Librarian Terri Sheridan, our resident historian, shared rare books and photos from our archive taken by William Leon Dawson himself.

Examining W.L. Dawson’s personal copy of the souvenir edition of Birds of California in the library. Only 35 copies of this edition were produced, exclusively for people who aided in the book’s production. Left to right: Keith Dawson, Katharyn Dawson, Terri Sheridan

Undated, unannotated photo by Dawson of unidentified nest in a pine tree. Intriguingly, the area appears to be flooded.

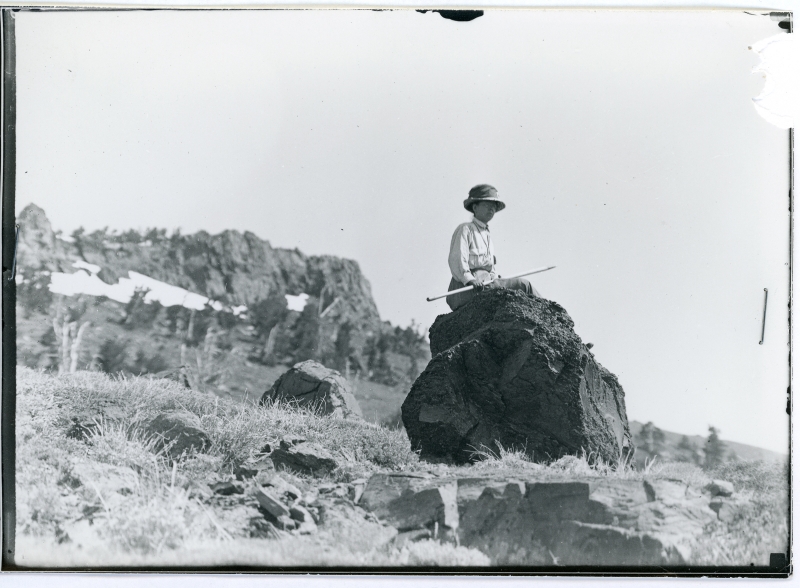

Critics complained that the images in Dawson’s first book Birds of Ohio left something to be desired, so Dawson took up all aspects of the photographic process himself, developing remarkable skill over decades. Many of his images are stunning, revealing not only a knowledge of his subjects but a flair for composition. His accomplishments are even more impressive when you consider the difficulty involved in photography during the early part of the century, when cameras were ungainly and photographers needed practical knowledge just to create images that were properly exposed and in focus.

W.L. Dawson’s portrait of his wife Francis Etta Dawson in the field. W.L.’s notes on the photograph read: “ ‘The Veteran’ Etta … Warner Range / Near Pinicola Camp / July 4, 1912.” Her determined pose is consonant with how Keith recalls his mother referring to Etta: as an individual with “spizzerinctum,” which Merriam-Webster defines as “the will to succeed.”

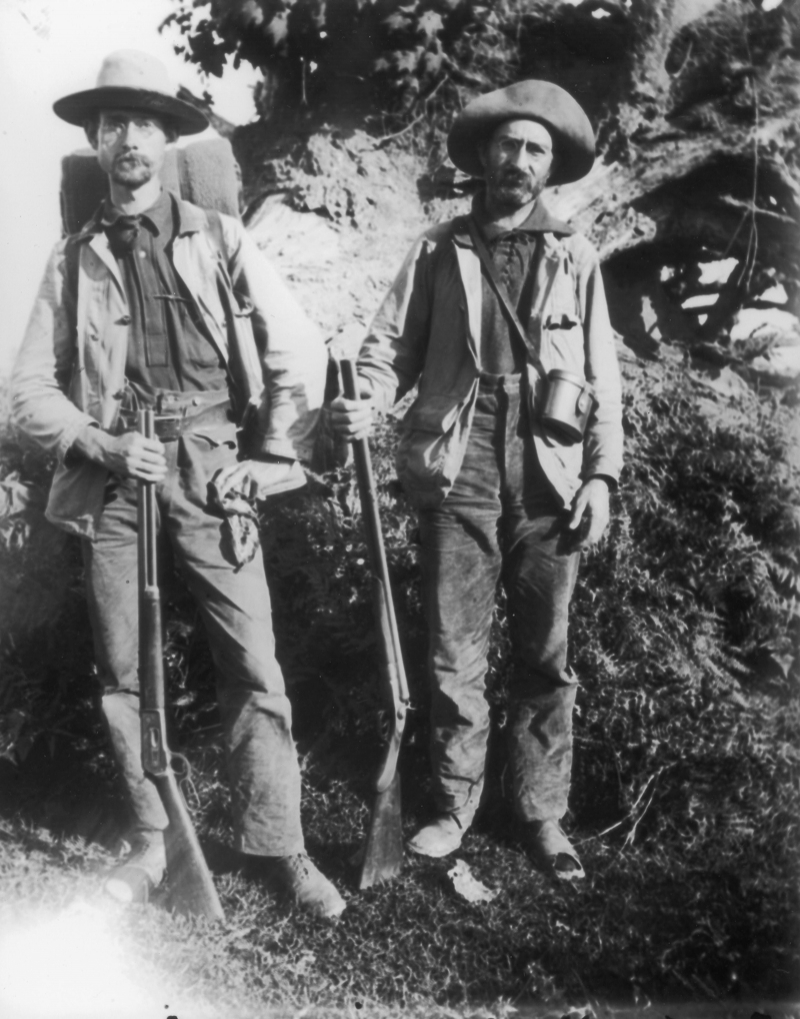

On top of the general difficulty of photography at the time, Dawson took his camera with glass plate negatives into field conditions that were awkward, dirty, and dangerous. In his pursuit of oological knowledge, he was prepared not only to develop new proficiencies, but to take physical risks. He scaled the heights of trees and precipices to recover nests and eggs. Dawson’s zeal was a cause of concern for family and friends, though for colleagues in the same business, it was the norm. His collecting trips—with partners like his Oberlin College professor Lynds Jones—took him to places where transportation and accommodations were rudimentary, during a time when scientists were accustomed to roughing it without the benefit of GPS or Gore-Tex.

Dawson and Jones outfitted for a turn-of-the-century expedition to the Cascade Mountains. Photo courtesy of the Oberlin College Archives

“They’re hanging off cliffs, and they have guns, what could go wrong?” Dr. Fahy shrugs. In 1932, Ralph Hoffmann—Dawson’s successor as Museum director—fell to his death on San Miguel Island while collecting botanical specimens. Fahy has warned her junior colleague Dibblee Curator of Earth Science Jonathan Hoffman, Ph.D., (no relation to Ralph Hoffmann) to watch his step in the field. We make it our business to know our history and learn from our mistakes. (Incidentally, that is how science works.)

This photo in W.L. Dawson’s collection captures a young man who appears to be his son (Keith’s father) William Oberlin Dawson climbing a dead tree in search of a nest.

Dawson’s own egg collection—collected at personal risk—formed the foundation of the collections of the Museum of Comparative Oology (MCO). He convinced fellow egg-collectors Rowland G. Hazard II and many others to add to the MCO’s collections. After Hazard’s death in 1918, his sister Caroline Hazard and widow Mary Pierpont Bushnell Hazard supplied land, funding, and guidance that led to the creation of a purpose-built museum where SBMNH exists today. Our entrance courtyard is composed of those original buildings.

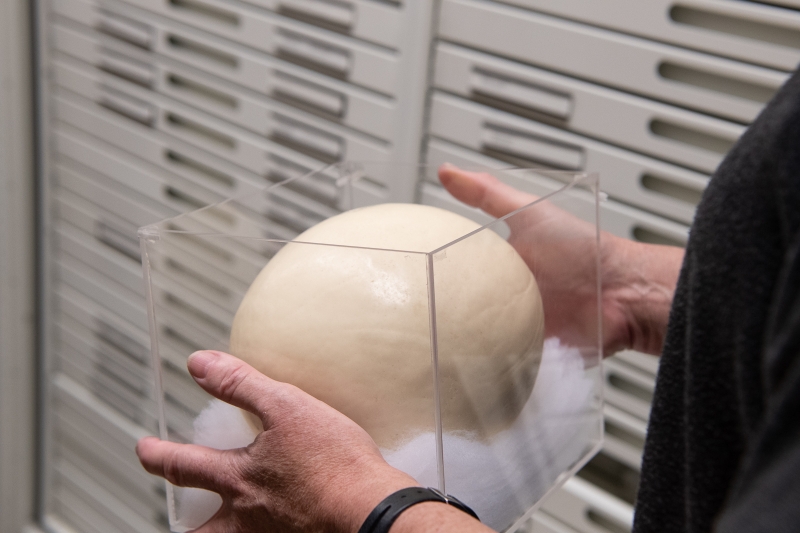

Fahy showed the Dawsons the Elephant Bird egg, originally part of Hazard’s collection. The Elephant Bird is the largest bird in the fossil record, and its eggs are extremely rare, as this bird has been extinct since at least the 1600s. (Fortunately, eggs, unlike nests, hold up well over time if carefully protected.) It was a tremendous coup on Dawson’s part to convince Hazard to contribute his valuable collections to the Museum of Comparative Oology.

Much has changed since Dawson’s era of collecting. The egg-collecting hobby fell out of vogue as awareness grew of the damage being done to bird populations by a variety of human activities, including overcollecting (particularly of birds whose feathers were used in fashion). Today, collecting eggs, nests, and bird specimens is heavily restricted, and rightly so. Researchers must compete for rare permits to collect, and have to demonstrate to permitting agencies that the knowledge they could glean from collecting specimens is worth the disturbance to nature.

This changing environment—and the changing regulatory environment it inspired—gives our collections an interesting shape. Their particular strength lies in providing a baseline from historic specimens—like those of Dawson’s time—which ecologists can compare to their sampling results today. Comparisons are only possible because Dawson—though he collaborated with amateurs—took a more scientific approach than hobbyists, carefully recording where and when he found his specimens. Without this information, specimens are—for the most part—merely beautiful paperweights. Provided with data, they can make us aware of trends over time and space, informing policies that change the world. With each passing year, we learn more from well-preserved specimens, as researchers leverage new technology to glean more information from them. (Perhaps you’ve already heard us harp on that, to the tune of whale earwax and stuffed birds.)

Keith holds a box containing tiny eggs from Leucosticte tephrocotis dawsoni, a subspecies of Rosy Finch named in honor of his grandfather by Joseph Grinnell.

With eggs collected by W.L. Dawson, foundational specimens in our oology collections. Left to right, Katharyn Dawson, Keith Dawson, Terri Sheridan, and Krista Fahy

We think W.L. Dawson would have been gratified to know that his obsessively collected, meticulously documented specimens continue to serve science a century later. He left the Museum under a cloud in 1923, when the leadership at that time determined there was strong community interest in expanding the institution’s focus to encompass all of natural history. Dawson—who wanted to stick strictly to oology—was forced to resign.

Egg specimens and cast touchables provoke contemplation, astonishment, curiosity, and concern from visiting schoolchildren and their parents (DDT affected eggs at far right)

Dawson probably would not have imagined thousands of schoolchildren visiting our campus annually, learning lessons from his specimens, and from specimens collected by those who followed in his footsteps. It is unlikely that he would have foreseen that the Museum would become home to some unique live birds, as it is today the home of rescued raptors in Eyes in the Sky, a program of the Santa Barbara Audubon Society. We wish he could return today to see how oology remains at the heart of an institution that has expanded in so many positive ways. Keith Dawson’s visit was the next best thing.

Meeting Kisa the Peregrine Falcon with a volunteer from Eyes in the Sky

4 Comments

Post a CommentOwen, thank you for the masterful writeup. And thanks to Krista Fahy and Terri Sheridan for the behind-the-scenes tour, and to museum president and CEO Luke Swetland for greeting us at the entrance. I never knew my grandfather but now I feel I have a better sense of his life and work.

Keith, you're very welcome! Thank you so much for visiting. I hope you and Katharyn will be able to make a longer visit sometime to dive deeper into W.L.'s legacy here.

I appreciate this well-written article by Owen Duncan, whose eye for aesthetics also may have contributed to the well-chosen photos. An excellent look at historical and contemporary offerings.

Owen, great writing and research on this story. I love reading about the Museum's incredible history!