Science Pub: Exploring the Deep Sea Aboard the E/V Nautilus

The Stubby Squid: Does it have a face only a mother could love, or the face that launched a thousand ships? However its gaze may strike you personally, it launched at least one ship, namely, the E/V (exploration vessel) Nautilus. The Nautilus belongs to the Ocean Exploration Trust, and it’s the ship that brought the world this astounding face from the depths…and much more. If you’ve been living your life somewhere even more remote than the Mariana Trench, and you’ve never seen the Stubby Squid or heard of the Ocean Exploration Trust, you’ve still probably heard of its founder, Dr. Bob Ballard. He discovered the Titanic, remember? What’s more, he’s a UCSB alumnus, and thanks to him, our region is treated to recurring brushes with greatness vis-à-vis the deep sea.

The congenitally surprised-looking Stubby Squid, which is more like a cuttlefish than a squid, really, though cuttlefish, in turn, are more cuddly than fishy. Call it by its proper name: Rossia pacifica. Photo credit: Ocean Exploration Trust

Attendees of our monthly Science Pub event at Dargan’s Irish Pub & Restaurant enjoyed some of that vicarious marine magic on May 14, when SBMNH employee and Ocean Exploration Trust Lead Science Communication Fellow Melissa Baffa shared her experiences aboard the Nautilus. Baffa has cruised—if you can call it a cruise when you’re working during every waking moment—with the Nautilus twice, and will voyage again this fall when the ship visits the Davidson Seamount in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. For Baffa, it’s been an adventure that fulfils a lifelong dream to do science and travel the world. Her first voyage on the Nautilus in 2015 took her to the Galápagos Rift—about 230 miles northeast of the Galapagos Islands—where the ship’s ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) dove to depths of about 2,500 meters (8200 feet). Dr. Ballard, now in his mid-seventies, joined this leg of the expedition, revisiting the hydrothermal vents he’d been the first to explore in 1977.

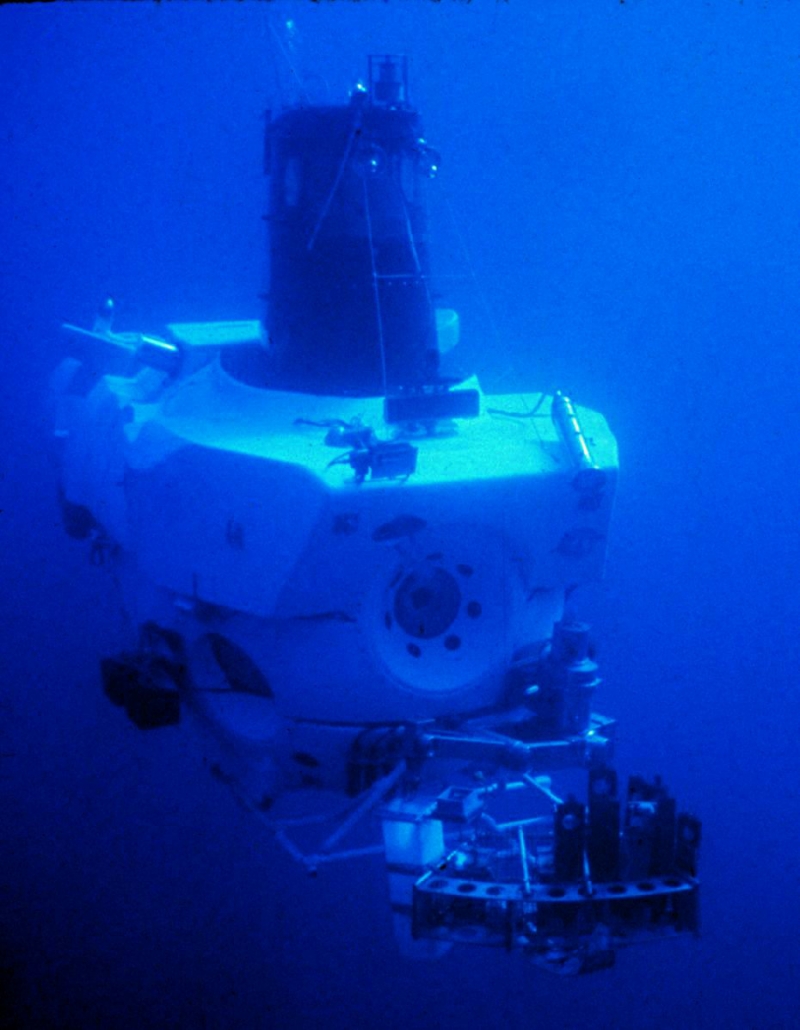

Ballard’s first visit to the hydrothermal vents of the Galápagos was very different from his return in 2015. In the seventies, the theory of plate tectonics had only recently replaced older models of understanding the earth’s crust and mantle. Geologists needed more information about areas where plates were moving apart under the sea, slowly creating new surfaces—about as quickly as your fingernails grow—as magma emerged and cooled. As a first foray, researchers from Scripps Institute of Oceanography towed a deep-sea sled with camera equipment and a thermometer over an area where seafloor spreading was suspected to be taking place, resulting in images that warranted further study. In 1977, Bob Ballard and colleagues dove to the same area in the U.S. Navy/Woods Hole/NOAA submarine Alvin and made a surprising discovery: the area was teeming with weird life. In Baffa’s words, “They had come across this incredible wonderland of all of these different creatures...eel-like fish and huge piles of what looked like clams and tubeworms, and all sort of things.”

Alvin (Photo credit: NOAA)

Finding life at that depth was so unexpected that the expedition to check out the vents didn’t include a single biologist: it was all geologists of one stripe or another (including UCSB’s plate tectonic specialist Tanya Atwater, then at MIT). After all, the vents aren’t a place you’d expect life. These are sites where cold water seeps down through cracks in the earth’s crust, becomes superheated by the magma down there, and then shoots back up and out. In these places, extremes coexist: you have very cold water in the depths, very hot water—and other unpleasant substances, toxic to most living things—emerging from the vents, and extraordinary pressure crushing everything. Most importantly, the sun’s rays don’t penetrate all the way down there, so the energy from the sun that forms the foundation of the food webs we know and love up above isn’t supplied in the depths. The expedition team was fascinated. Why would there be life? What would support it?

“They got their first clue when they got everything topside and they opened up those water samples,” said Baffa. “The smell knocked them either out the doors vomiting over the sides, or throwing open portholes as quickly as they could.” It was the rotten-egg smell of hydrogen sulfide, suggesting that they’d discovered the first evidence on earth of something that had only been discussed at a theoretical level: the existence of an entire community based on chemoautotrophs, organisms that make their own food from chemicals. The energy source supporting the base of the food web was the hydrogen sulfide contained within the clouds of “smoke” billowing up from the vents. Tiny organisms were subsisting on it, larger ones were eating them, or living symbiotically with them, and so forth…and none of the creatures down there knew or cared about the sun. It was as astonishing as discovering life on another planet.

The Alvin expedition team wasn’t equipped with enough formaldehyde to preserve all the biological samples they were unexpectedly taking, so they drew on the stash of vodka they’d picked up in Panama. Meanwhile, the implications of their discovery moved out like ripples. Could life on earth have started at hydrothermal vents? What about life on other planets? Could that look more like deep-sea vent life than the communities we see on land? Baffa reminded us of how space-conscious we were in 1977, when the Voyager spacecraft (carrying the famous golden record of “The Sounds of Earth”) was launched. Since then, different vent/seep communities have been discovered around the world, all showing variations on the theme of life based on breaking down chemical bonds.

The Flamboyant Squid Worm, one of the unearthly deep-sea creatures captured by present-day explorers on the Nautilus ROV cameras. Photo credit: Ocean Exploration Trust

Baffa extended the deep-sea/deep space metaphor throughout the evening. It’s an apt comparison for many reasons: the dangers faced by human explorers, the extreme conditions, and the challenge of building an understanding of a vast area based on small samples. To visualize this latter difficulty, Baffa prompted us: “Imagine going into your backyard with a drinking straw, and looking through the straw, and then extrapolating from what you see through the straw about what life on your planet is like.” She and fellow Nautilus team members would joke that for all they knew, outside the scope of the lights and cameras mounted on their ROVs, there could be a UFO hovering outside of every shot.

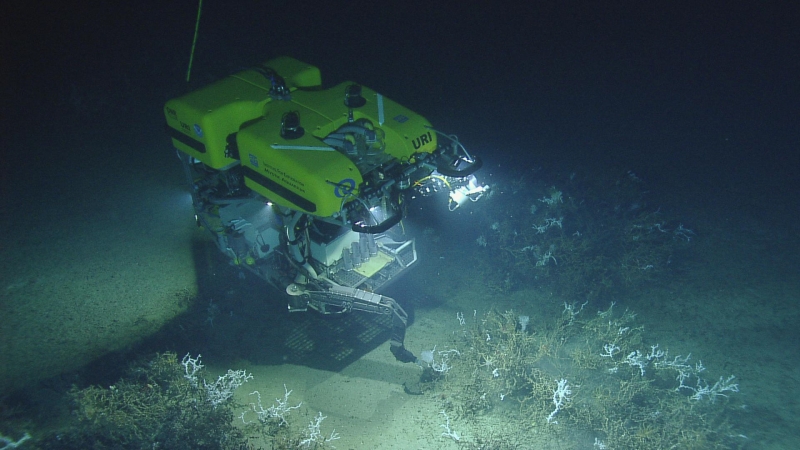

ROV Hercules collecting biological samples, which will be held in collection at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, and available for the scientists of the world to study. Photo credit: Ocean Exploration Trust

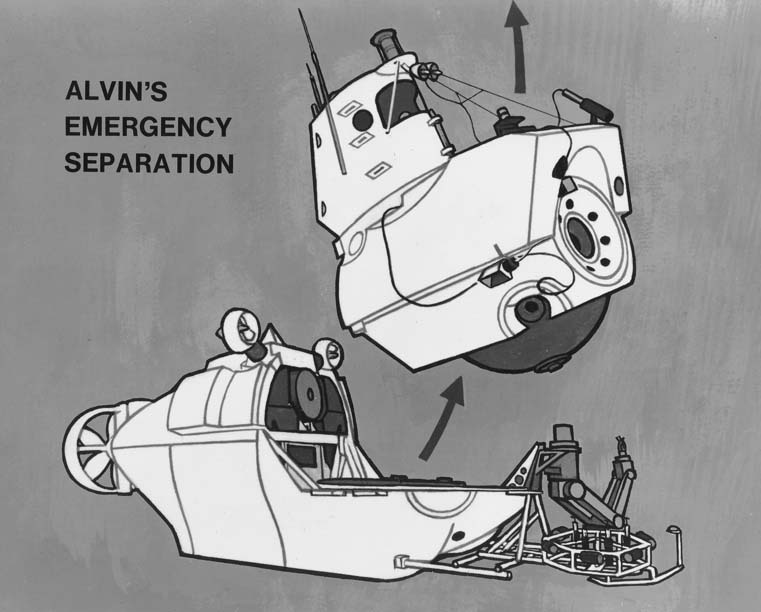

Still, we’re talking about state-of-the-art drinking straws here. Every time Ballard and colleagues piled into tiny Alvin, they set out on a great adventure, but their efficiency as scientists was harshly constrained by the limitations of the human body. The sub had to be slowly lowered to depth—and slowly raised—bookending a very short amount of time left for exploring the seafloor. Baffa compared it to “being lowered in an elevator for one-and-a-half, two-and-a-half hours,” with the same tedious commute on the way back up. “So in an eight hour dive, you may only get three hours on the bottom. Not very efficient. And this whole time, if one small thing goes wrong, you might die.” Today, robotics technology allows vigilant researchers to work around the clock, rotating in and out over a four-hour watch cycle, while the ROVs stay down for up to three days.

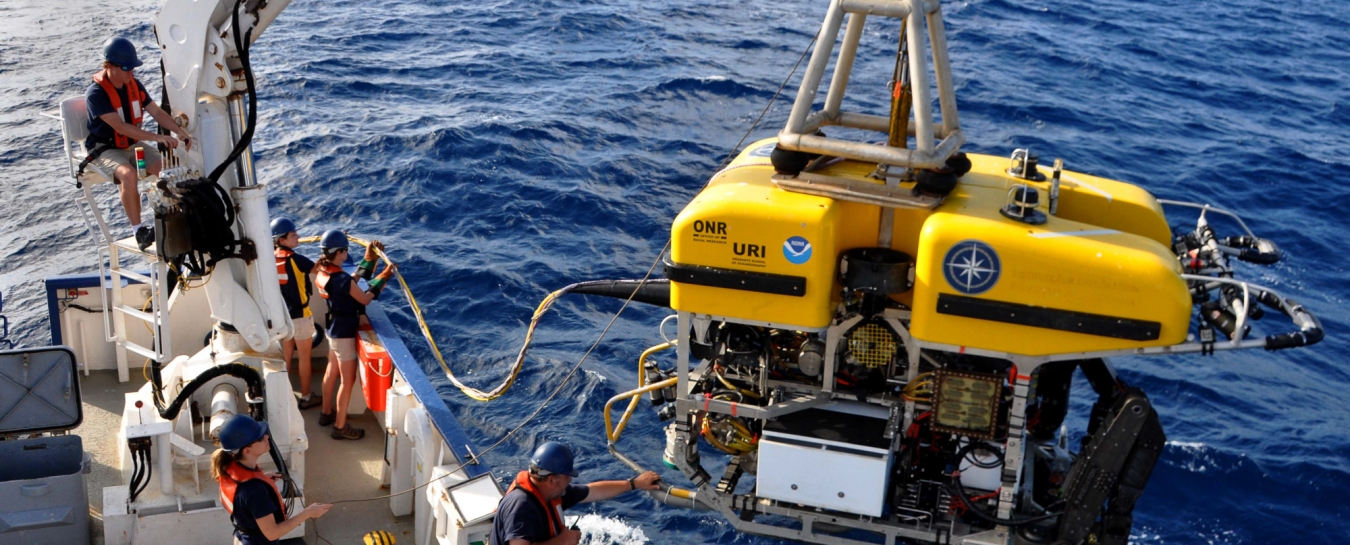

Argus and Hercules await their next dive, off Catalina Island, in 2016. Photo credit: Melissa Baffa

The Nautilus explores the deep with two ROVs, Argus and Hercules. Argus, affectionately known as “the dope on the rope,” is gently towed behind the ship, and serves as an extra pair of eyes and a shock-absorber. As the Nautilus rocks with the swells on the water’s surface, some of that jostling is transmitted down the support lines that run to the ROVs. Those destabilizing forces encounter Argus first, and that robot acts as a buffer, so that the nimbler ROV below—Hercules—can stay relatively steady. This produces smooth camera footage, and helps Hercules maneuver and sample safely. Argus also bears additional lights and cameras to support Hercules.

Hercules is, in Baffa’s words, “all tricked out” with sampling equipment, including tools for taking water and sediment samples. It has two arms, and they’re a bit like the claws of a fiddler crab: one is designed for tasks requiring dexterity, while the other is built for brute force operations. Still, you wouldn’t want to mess with either: even the delicate one has a gripping force of 6,000 pounds per square inch. Hercules also has its own high-definition cameras and lights.

Hercules looking every inch the pimped-out ride. Photo credit: Ocean Exploration Trust

Hercules is rated to dive to a depth of about four thousand meters (over 13 thousand feet). Thanks to fiber optic cable and satellite communications technology, the information Hercules gathers only takes about “20 seconds [to get] from the bottom of the sea to your cell phone.” And that connection isn’t just hypothetical: sharing is the Nautilus modus operandi. Once their exploring season begins (this year, they start to dive around June 12), you can keep up with their discoveries on Nautiluslive.org. As Baffa says when she shares the site with anyone, “I’ll say two things: you’re welcome, and I’m sorry…because it’s really addictive.” Don’t visit the site unless you’re prepared to have your day hijacked by the likes of an adorable Stubby Squid or Dumbo Octopus.

Once you’ve enjoyed the unique cocktail of cute and weird that is deep sea fauna, you can react to it via the site’s chat function. One of Baffa’s duties on Nautilus is to interact with site visitors like you, who write in via chat. When on watch, Science Communication Fellows help to engage the global audience and answer questions, weaving the queries submitted through the website into the flow of conversation among the researchers and ROV pilots conducting the dive.

Baffa’s been deeply touched by the inspiring and surprisingly intimate encounters that result. The Nautilus team members share amazing moments with viewers, but what people share back is sometimes equally astounding. Baffa was deeply touched when a man in Italy reached out to tell her he was translating the Nautilus live feed to his dying father, as they shared some totally unique quality time. They started up a conversation in which it wasn’t clear who was more amazed: the researchers who were suddenly part of a stranger’s final moments, or the dying man who was astounded that deep-sea explorers halfway around the world would care enough to communicate with and honor him. “Beyond the science, and beyond the wow-that’s-cool, we’re connecting people.”

In addition to mediating exploration and live chat, Baffa helps run live interactions between Nautilus and institutions such as museums, zoos, and schools. Over the course of the year, this outreach program serves about a million people annually, and it’s just a small part of all the OET does to promote exploration and science.

Baffa honing her live interaction skills during a training at the Inner Space Center at the University of Rhode Island, Graduate School of Oceanography (the hub through which the Nautilus internet feed passes). Photo credit: Ocean Exploration Trust

Since—as Ballard puts it—only the “human spirit” is being sent to the bottom of the sea, Baffa and the other expedition staff do their work in relative comfort. “When you’re on watch, you come up to the control van, which is two cargo containers welded together,” Baffa described. While the accommodations are more comfortable and spacious than Alvin’s, those reporting for duty have to bundle up, because the van is kept at arctic temperatures to keep all the equipment running happily. Baffa sits up front, next to a video technician, the two ROV pilots, and the navigator. They’re accompanied by scientists who direct the dive and log data, and sometimes by Dr. Ballard, who’s often so excited he can’t sit down. At 6’3”—taller than the interior of Alvin—it’s possible he relishes exploring the deep in a space where he can stand up.

Dr. Ballard, standing behind Nautilus science team members in the control van during his first return to the hydrothermal vents he discovered in 1977. Photo credit: Melissa Baffa

The ROV pilots in the control van range from legends like Alvin and ROV pilot Will Sellers to rookies fresh out of MIT. There are opportunities for people of all ages to get involved on the Nautilus, and Baffa has relished watching her younger teammates grow as individuals as a result of on-the-job training. Over the course of her voyages, Baffa has watched young ROV pilot Jessica Sandoval grow. In her first year, Sandoval was nervously learning to control Argus. When Baffa next worked with her, she’d moved on to Hercules. Using Hercules’s robotic arms, the greenhorn maneuvered delicate deep-sea clams into the sample box without breaking a single one. “To see her pull that off was amazing,” Baffa beamed. When the clams were brought to the surface, some of the people working with them accidentally crushed the delicate shells with their bare hands, but Sandoval had manipulated them with the robot arm with the abovementioned gripping power of 6,000 pounds per square inch! If this sounds like your kind of job, be aware that working with the OET on the Nautilus isn’t for the faint of heart. Baffa reports that, fittingly, “they train [interns], but then they really throw them in the deep end.”

The science communication fellowship program Baffa taps into is open to both formal and informal educators. When Baffa first got the opportunity to be a science communication fellow with the Ocean Exploration Trust, she was working for Girl Scouts of California’s Central Coast as their Director of Outdoor Experience and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math). Baffa only learned about the Nautilus fellowship because of a misunderstanding about a forwarded email from a random mailing list. Her supervisor quickly scanned the Ocean Exploration Trust’s call for intern and fellowship applications, and misread it as a resource from which the Girl Scouts might source their own interns. Baffa read the email more carefully, and learned it was a chance to realize a childhood dream she’d long deferred.

With only two days before the deadline, she whipped together an application, writing her own letter of recommendation at her boss’s request. She asked her husband if he could handle parenting alone for a stretch, if she was accepted. He could tell how much the opportunity mattered to her, and acquiesced. It’s a real challenge: “The first year that I sailed,” said Baffa, “I went out for three and a half weeks, which is a long time to be a single parent if you’re not used to it.”

The sun sets behind the crags of Catalina Island. Photo credit: Melissa Baffa

Career-wise, she blended her day job with her adventures on the Nautilus by creating programming for Girl Scouts about STEM careers and deep-sea exploration. Baffa now works for the SBMNH in the Development Department, and the overlap between her work and her voyages remains strong. Here, she works to secure grants for the Museum, and that involves telling the stories of people in STEM and museum careers. She has to bring these stories alive for representatives of funding institutions who—like Girl Scouts—may not have a ton of technical knowledge about the issues concerned, but can easily understand what’s at stake if the story is told the right way.

Baffa’s own story is illustrative of how careers in science needn’t be linear or confined to the well-known roles of industry researcher or college professor. She majored in biology at California State Lutheran University, where her professors discouraged her from pursuing a career as a high-school biology teacher. They felt that Baffa—a promising student—wouldn’t be reaching her potential if she taught at a lower level. So they encouraged her to continue on to grad school, and she applied to UCSB’s Marine Ecology program. Meanwhile, an old classmate tipped her off to an opportunity to work for Amgen, a biotech firm based in Thousand Oaks. In the end, she had to choose between struggling to support her family on a graduate student’s stipend and making a real living working in industry. “I figured once we paid for rent and childcare, we’d have nothing to eat, no[thing to cover] healthcare expenses, no anything.” Baffa was burnt out “after four years of working two or three jobs at a time, eating lots of beans” to get through college, so—with regret—she took the job rather than the grad school opportunity.

The position was in a DNA sequencing lab where she performed the same tedious tasks day after day. “It was monkey work. You know, you put the chemicals in, you put it in the machine, you go to the computer… Once you got it, it was so monotonous. And molecular biology wasn’t really the thing that got me excited, anyway.”

After about three years, she’d had enough. With the support of her then-boyfriend (later husband), she was able to leave industry and go into the field she’d always considered: teaching. She took a pay cut and lost stock options, but renewed her sense of purpose, teaching middle school and high school for about a decade before taking up educational roles in the nonprofit sector. Who would have thought that seventeen years later, she’d end up as a headshrinker?

Baffa with famous heads Diego and Pedro at Science Pub.

Yeah, about that. Remember we mentioned the pressure conditions in the deep? As you dive, you’re under increasing pressure from the water around you. Baffa reminded us that “it’s why your ears hurt when you dive in the deep end of the pool.” This is where the head-shrinking comes in. Baffa reports: “It’s really typical with people who are doing this kind of deep-sea exploration to shrink Styrofoam objects. Usually it’s a coffee cup [which becomes a] shot glass.” But Styrofoam cups come in different sizes, so when you shrink one, it’s not always clear how much it’s changed. Styrofoam heads are all roughly head-sized, and shrinking them is a lot more fun. A head can take on personality and charisma that a coffee cup could never achieve. Take Rosie, the first head Baffa shrank. A vintage wig head Baffa found at a thrift store, Rosie didn’t compress evenly: “Her head was all cocked to one side, her eyes were swollen, and her nose was smashed; she looked like a boxer!”

The effect is best when you can compare a “before” and “after” pair of heads. In 2016, using two heads named after ports—[San] Diego and [San] Pedro—Baffa ran a social media campaign, encouraging people to vote to determine which would be subjected to the pressures of the depths. “Pedro won…or lost, depending on how you look at it.” Pedro and Diego sport irresistible mohawks made of unraveled nylon rope, a decoration suggested by Will Sellers. People love interacting with these heads: marveling at them, holding them to compare their densities, and just taking silly selfies. It’s probably one of the most fun ways you could demonstrate conservation of mass and the astounding pressure conditions of the deep sea. It’s also economical: the heads hitch a ride in a mesh laundry bag zip-tied into a milk crate strapped to the aft end of Argus.

One of the attendees who sought a selfie with adventuring heads at Science Pub.

The Nautilus team—in conjunction with National Geographic Kids—once recorded a cup-shrinking with their cameras, but that cup was attached to the front of Hercules, where cameras are easily trained. That area is prime real estate, so don’t expect to see heads appearing like hood ornaments on Hercules anytime soon…even though it’s undeniable that’d be more fun to watch than a shrinking cup!

Baffa’s still considering appropriate names for two of the three heads that will accompany her on her next Nautilus tour. Baffa will join the expedition from October 19 to November 1, when the ROVs dive at Davidson Seamount in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. So Davidson, Monty, and Ray are all possibilities, but she’s open to input. One head—the one reserved for Baffa’s personal collection and storytelling purposes—has already been named Barbara, for obvious reasons. Attendees at Science Pub added signatures and decorations to Barbara, who was looking quite glam by evening’s end.

Beyond Baffa’s cruise, there are some exciting destinations on tap for this season. In addition to returning to our own Channel Islands, the Nautilus will explore methane seeps in the Pacific Northwest, try to find evidence of arch volcanism near Hawaii, and even visit “the next Hawaiian island,” the underwater volcano Lōʻihi Seamount. There, the OET team is collaborating with NASA and NOAA as part of the SUBSEA (Systematic Underwater Biogeochemical Science and Exploration Analog) Research Program, in order to develop practices and technology for exploring oceans on other planets. The season—the second-longest for the Nautilus—starts in early June and runs through November.

Baffa addressing a packed house at Dargan's

If you’ve struggled to join us at Science Pub in the past—it’s notoriously difficult to snag a seat unless you come very early—try coming in June, when there are typically fewer folks in attendance due to finals and graduation ceremonies. This year SBMNH Director of Education Justin Canty will address the problem of nature deficit disorder and share the preliminary results of a study on nature-based play conducted in our own Museum Backyard. Learn more on the event page.

If you read this whole thing, you deserve the treat of seeing how Alvin was like a tiny USS Enterprise. Mr. Ballard, make it so! Illustration credit: Office of Naval Research

Top-of-page photo: Crew launching Hercules during Baffa’s first voyage on the Nautilus. Photo credit: Melissa Baffa

0 Comments

Post a Comment