Tom Dibblee

Thomas W. Dibblee, Jr. (1911–2004) was an incomparable field geologist with a mapping career that spanned seven decades. His first encounter with geologic mapping came in high school, when he shadowed geologist Harry R. Johnson as Johnson mapped the 20,0000-acre Dibblee family ranch, Rancho San Julian. Young Tom produced his own geologic map that summer, the first of many Dibblee maps that would cover over a quarter of California (>40,0000 square miles).

A suite of innate skills aided Tom Dibblee’s remarkable work. Tom had an excellent memory and recognition of visual patterns, as he demonstrated as a teenager on a roadtrip to Bakersfield with his father. On that trip, Tom noted rock sequences in the Tehachapi Mountains that he correlated to outcrops on Rancho San Julian. Tom also possessed an inexhaustible ability to traverse harsh terrain, which he developed on Rancho San Julian and used to impress countless colleagues over the decades.

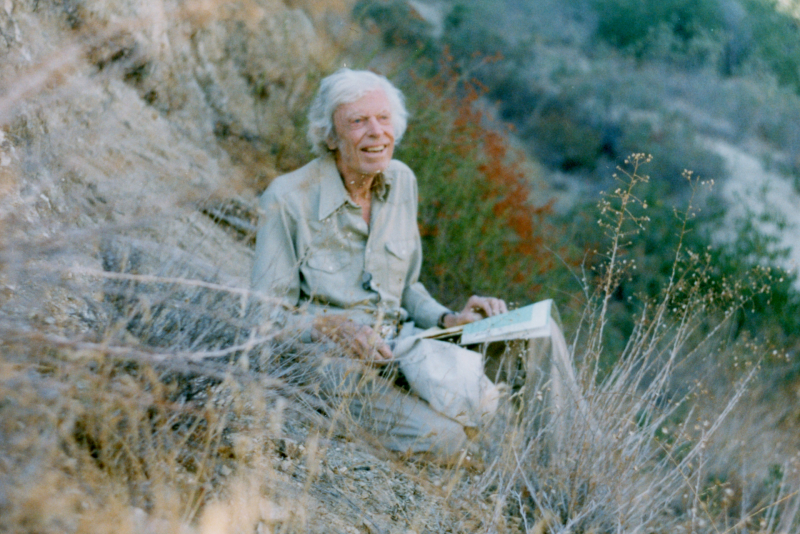

Tom Dibblee in the field. Photo by Mary Bates

Following his graduation from Stanford with a bachelor’s degree in geology in 1936, Tom Dibblee worked for the Union and Richfield oil companies. It was with Richfield that, in 1948, Tom predicted the presence and location of oil in Cuyama Valley. His recommendation resulted in the production of about 300 million barrels of oil from the Russel Ranch and South Cuyama Oil Fields. The Dibblee Sands unit of the Vaquero Formation was named in his honor.

Tom’s field work with his Richfield supervisor Mason Hill would produce research fundamental to our modern understanding of Southern California’s geologic history. Based on Tom’s mapping of a 50-mile-wide swath along the San Andreas Fault zone from Coachella Valley to the San Francisco Bay area, Hill and Dibblee (1953) proposed right-lateral displacement of more than 350 miles along the San Andreas since the Jurassic. They noted striking similarities between distantly exposed rock sequences, like the Cretaceous sedimentary rocks of the Temblor Range and the strata near Fort Ross, 320 miles to the northwest. Hill and Dibblee proposed the offset of these strata more than a decade before a mechanism would be provided with the formal proposal of the theory of plate tectonics.

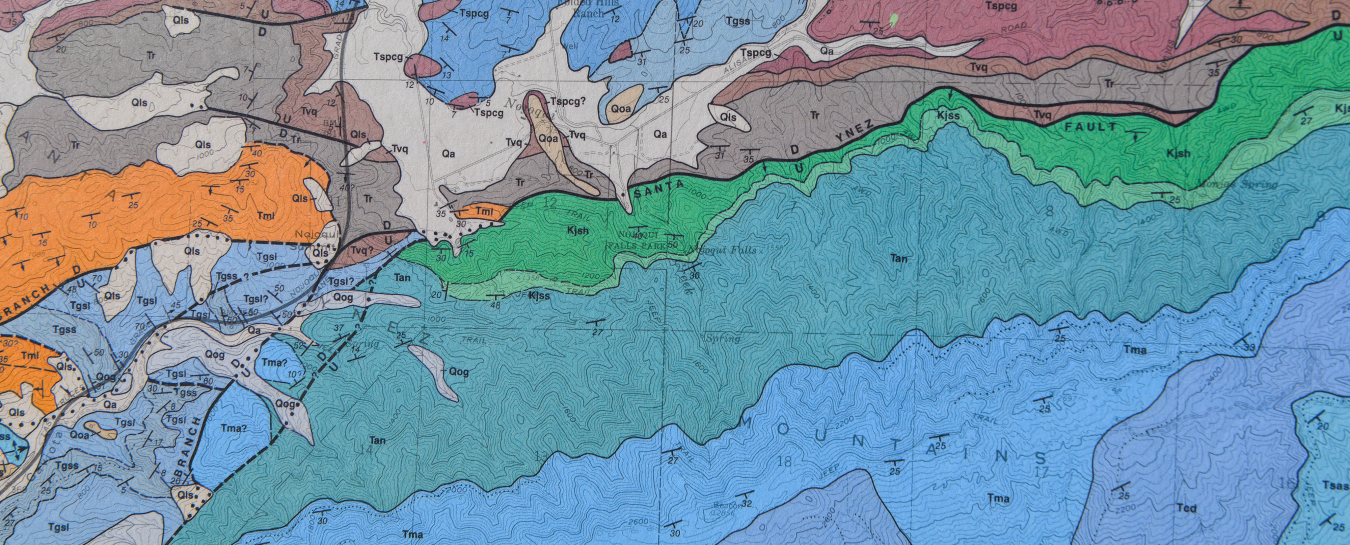

Following his success in the oil industry, Dibblee achieved his lifelong dream of working for the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 1952. Tom worked for the USGS for 25 years and, among other projects, mapped about 7,000 square miles of the Mojave Desert to inventory boron deposits for rocket fuel. The massive project would take over 10 years to complete and consisted of 40 different 15-minute quadrangle maps. After his retirement in 1977, Dibblee volunteered to map 1.2 million acres of Los Padres National Forest. The project took six years and produced 106 different 7.5-minute quadrangle maps. For his efforts, Tom was awarded the Presidential Volunteer Action Award from President Reagan in 1983.

In 1986, friends and colleagues formed the Dibblee Geological Foundation with the explicit mission of preserving the scientific, technical, educational, and economic values of Tom’s life work through timely publication. Previously published maps were updated by Dibblee and colleagues, and provided a uniform scale and standardized colors and formats. In total, 419 updated Dibblee maps were published by the Dibblee Geological Foundation. As he explained to many admiring geologists on “Day in the Field with Tom Dibblee” trips, his methodology was relatively simple (map the lithology and only exposed or clearly evident faults) and reliant on his excellent memory to quickly recognize rock units and correlate stratigraphic columns. The results were prolific: efficient mapping with structural interpretations that are still accepted today. Over the last 30 years, the Dibblee maps have informed and benefitted numerous California industries, including mining, energy development, engineering and land development, environmental consulting, and insurance.

In 2002, Tom Dibblee bequeathed his estate to the Museum to start the Dibblee Endowment and Dibblee Geology Center. He had lamented that his hometown museum lacked a geology program and, when announcing the bequest, he said, “The Museum means so much to me. This is the happiest day of my life.” Tom remained productive past his ninety-third birthday. In November of 2004, he lost his eyesight literally overnight, preventing him from working on his beloved maps. Tom Dibblee passed away ten days later, on November 17, 2004. Today, the Dibblee Geology Center at the Museum is dedicated to Tom Dibblee’s ideals of advancing knowledge of the Earth through research, providing expert geologic advice to both public and private interests, and advancing public education in geology.

—Biographical text by Dibblee Curator of Earth Science Jonathan Hoffman, Ph.D., and former Dibblee Geological Formation Member Susie Bartz